This article is more than 1 year old

Google on Google: The carefully collated anti-trust truth

Never leave a baby in charge of this sort of thing

Google doesn’t always take the threat of anti-trust charges too seriously. After the Wall Street Journal implied that the FTC opted for less aggressive action against Google because of political pressure, Google responded with references to a laughing baby, and by personally attacking the newspaper’s owner.

After all, when you’re more powerful than governments, why would a government worry you?

But while responding with derision is one thing, presenting questionable evidence to investigators is another.

Rachel Whetstone, Google's former PR bigwig, and now in a similar role for taxi app Uber, responded to reports of anti-competitive conduct by posting a GIF of a baby on the company's official blog.

Then, on April 15, Google published a defence of its activity. It showed a thriving marketplace giving consumers a wide range of choices: “Numerous other search engines such as Bing, Yahoo, Quora… and a new wave of search assistants like Apple’s Siri and Microsoft’s Cortana.”

Google correctly states that:

Any economist would say that you typically do not see a ton of innovation, new entrants or investment in sectors where competition is stagnating – or dominated by one player.

However, Google price comparison rival Foundem has found some interesting things about the evidence presented in this post.

Baby: Unconcerned

Google actually leads by presenting a graphic of traffic to Google Travel, which isn't part of the European Commission's complaint. Google Travel was only launched in Europe in March 2013. The “rivals” in this chart are travel agencies, and most now pay Google Travel for referrals – they have to. But we'll put that to one side.

Google's data supposedly shows that it barely had any impact on an e-commerce market led by Amazon and eBay, with these two merchants dwarfing Google’s traffic in the UK and Germany, and Amazon and a host of smaller rivals grabbing the traffic in France.

This is plain weird, Foundem says, since a shopping site isn’t a price comparison site. Shopping sites do end-to-end business, taking you through to a completed transaction. Several years ago, Foundem was a much-lauded price comparison site – the whole point being it found you somebody who could sell something, and didn’t do that itself. So including giants like Amazon and eBay isn’t a like-for-like comparison.

Indeed, the European Commission couldn’t be clearer about why it’s filed a Statement of Objections: Google “systematically favoured its own comparison shopping product” and helpfully provides a paragraph explaining what one is.

Google also includes marketplaces such as Etsy and AliExpress – which are not price comparison sites either – as well as, bizarrely, Which.co.uk. Once you remove the likes of Amazon, eBay, Etsy and AliExpress, none of which are price comparison search engines, something interesting happens.

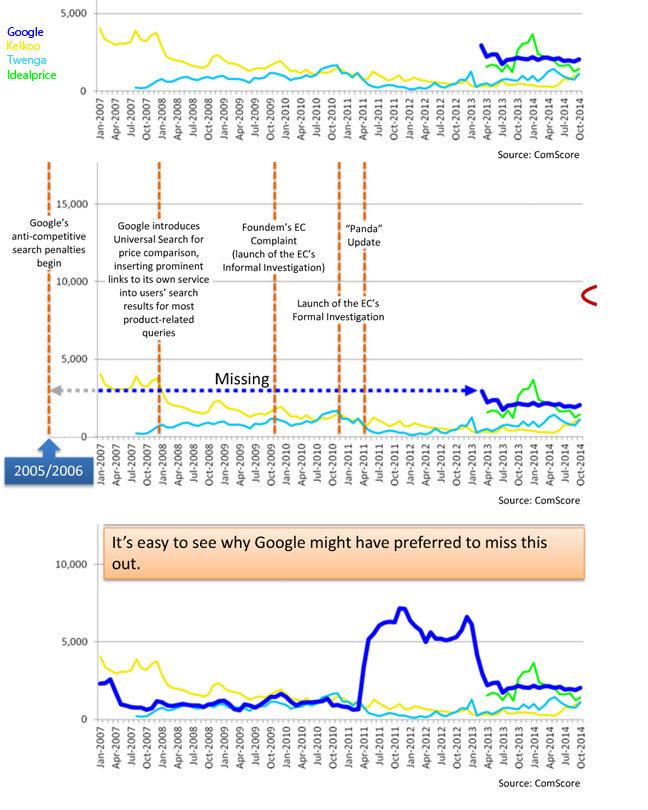

Firstly, Google only draws itself selectively, including data from 2013, 11 years after Google Shopping launched. Google rebranded Google Product Search as Google Shopping in 2013, which is why the data starts then.

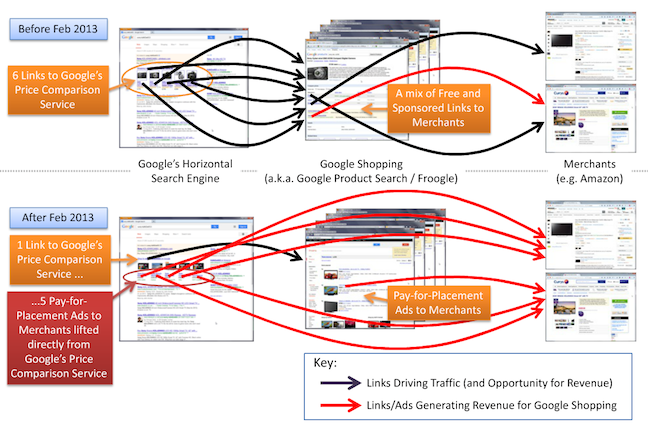

The peak in April 2011 was Google’s Panda update, which wiped out the comparison site competition. The decline in early 2013 was when Google opened up paid placement alongside its “organic” shopping results. Separated by a barely visible light grey line, Google listed advertisements from retailers in the same format as results from its comparison search engine. This diverted traffic away from rival search sites to the retailers themselves – or at least, the ones who wanted the traffic.

We’re not done yet, for there’s another striking example of selective evidence. Google shows three comparison sites, all of which show a suspicious uptick. One, IdealPrice, appears to have entered the market in 2013 – and surely an example of a new entrant is a sign of healthy competition?

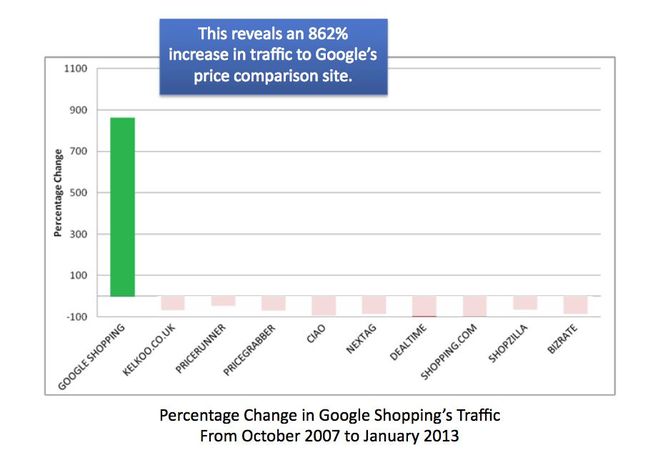

But what Google omitted were the price comparison engines that suffered during the period the European Commission is examining: Pricegrabber, Shopping.com, Dealtime, Nextag, Ciao, Pricerunner, Shopzilla and Bizrate. Include those, and the graph looks like this:

The average loss in traffic between October 2007 for the nine rivals Google omitted was 79 per cent, with the top three losing over 95 per cent. Google’s own traffic rose by over 200 per cent. Between 2007 and 2013 – when Google Product Search really turned into a billboard for retail ads – Google traffic rose 862 per cent.

Not everyone cares about price comparison sites – but that’s besides the point here. If the internet economy allows interesting new ideas and companies to compete on merits, and moves faster than the pace that a tiny handful of giants allow, then regulators have to do something difficult about the gatekeepers.

The Register has contacted Google for comment, and is awaiting a reply. ®