This article is more than 1 year old

New Horizons: We've got a pretty pic of Pluto. Now let's get our SCIENCE on

Why this three-bn-mile journey was worth it

Comment With everyone going ape over the dazzling new crisp pictures from NASA's New Horizons probe of the dwarf freezeworld Pluto, there are few voices asking if it was worth sending out a space probe to the far end of the Solar System – but it wasn't always that way.

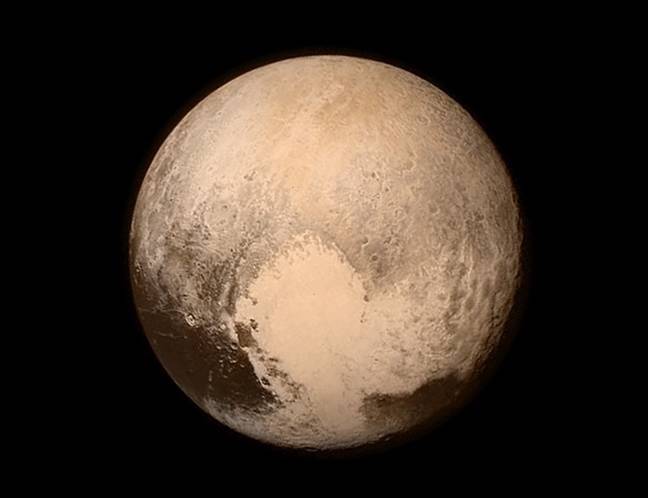

The eighth dwarf ... Very latest snap of Pluto from New Horizons

When a journey to Pluto was first mooted in the late 1980s, there was a lot of criticism of the idea, both within NASA and definitely within US Congress. After all, it's a small rock in the middle of nowhere – what's the point?

Even as New Horizons got closer, there were naysayers bemoaning the cost of such a mission ($700m, since you asked). Never matter that the entire program costs less than three F-35 fighters – some seem to think that we aren't getting enough bang for our buck and aren't there bigger fish to fry.

While it's fascinating that we're seeing close-up images of another planetary body for the first time, there's a hard science element to the mission that can sometimes be ignored. The fact is, New Horizons has already delivered enough useful new science to justify the time and money spent on the program, and will carry on paying its way for years to come.

Even before the probe had left the laboratory, the scientific payback was starting to come in. New components had to be developed and new materials were needed to get the probe small enough for an easy launch and tough enough to survive the journey. The whole thing had to be engineered into a small, power-efficient package.

As for the trip itself, the nine-year trek has been a learning experience for scientists, and one that will be crucial to future missions. To get the New Horizons probe going fast enough to get out to Pluto in a reasonable time was impossible under the mission constraints, so NASA had to get creative and use other planets for help.

It was probes like New Horizons that demonstrated you could use the gravity of a planet to boost a craft's speed – Voyager 2 got gravity assists from Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune – but this mission has been one of the longest experiments in doing so thus far while still maintaining accuracy.

Now the fun really starts

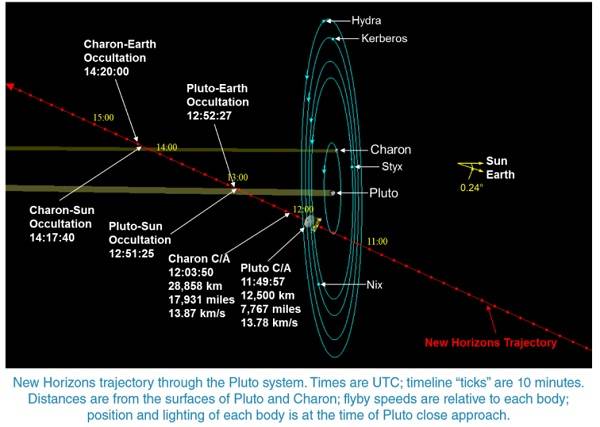

Consider the distances involved. NASA threw a probe over three billion miles through the Solar System, using the gravity from our largest planet to get it up to speed, and has now slung it past Pluto so close that it's less than an Earth-width distance away. Its relatively puny thrusters have given fine tuning abilities, but the mechanics of such a feat are immensely complex.

As a European by birth I should point out that New Horizons isn't the best example of this so far. The ESA Rosetta probe is, in many ways, a more impressive feat in catching up to a comet, but future NASA missions will benefit from the knowledge New Horizons has gained.

Now that we're at Pluto the fun really starts. We know now how large the planet is – something that previous observation had miscalculated – and we've found more moons around the dwarf planet because of the trip.

In particular, it now seems that Pluto's moons were formed in much the same way as ours were, according to current data. Pluto appears to have suffered a massive impact from another body, causing its moons to form.

Knowing this sort of data is crucial to cosmological theory about how the Solar System was formed. If that's too obtuse for you, understanding cosmology can also give us good ideas as to where to find different types of materials that could be useful to mankind.

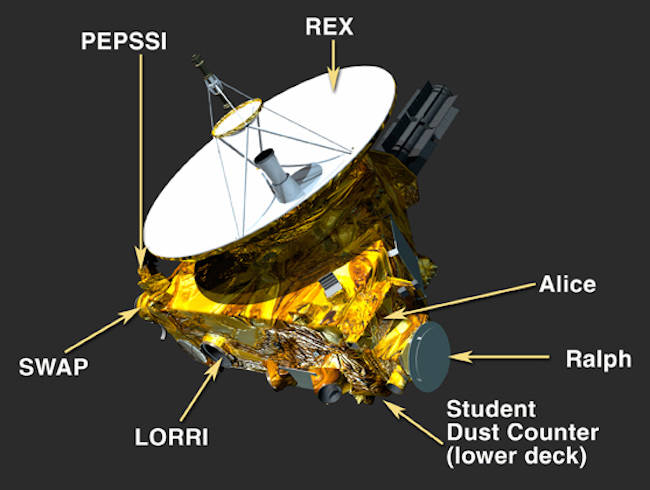

What's onboard ... New Horizons probe, which is about the size of a grand piano

Onboard the craft, there's Alice (a spectrometer for analyzing Pluto's atmosphere), Ralph (an instrument for mapping the surface), REX (which will search for an atmosphere on Pluto's moon Charon), LORRI (New Horizons' telescope and digital camera), SWAP (an instrument to measure the solar wind coming from the Sun), PEPSSI (an spectrometer to detect material leaving Pluto), and SDC (a dust detector).

All will provide valuable data for boffins back on Earth – you can find the technical specifications of these instruments right here.

As for the pictures themselves, there's a lot that can be divined from them in terms of understanding the geology and makeup of Pluto. Those pictures are important, but probably less so than the other suite of instruments aboard that will sample Pluto's environment and send back news about what makes this distant body tick.

By an unplanned coincidence, 50 years ago to the day Mariner 4 became the first man-made satellite to fly past Mars. Half a century on and serious minds are plotting to colonize the planet. As NASA says, with planets there are three stages of exploration: flyby, orbit, and landing.

During its brief visit, New Horizons will collect 5,000 times as much data as its predecessor, and send it back to Earth to help our understanding of the mysterious dwarf planet. It's unlikely mankind will want to land on Pluto, but we might want to put an early warning system out on the periphery for comets, and this probe is the first stage in that.

There's even the utterly minuscule chance that we might find something world-changing on Pluto – plenty of science fiction writers have posited that Pluto could harbor extraterrestrial surprises and, while it's a 99.999 per cent recurring long shot, you never know until you look.

But all of this is secondary to one single point behind the New Horizons mission – we went to Pluto because it's there and humans are endlessly inquisitive. If we weren't, we'd still be roaming the plains of Earth as just another primate. ®