This article is more than 1 year old

Malware menaces poison ads as Google, Yahoo! look away

Booming attack vector offers mass malware distribution, stealthy targeting

The pitch

Malvertising is a parasite that feeds on the popularity and trust of big-name websites, notably news publications. Advertising on these big-name web assets offers malvertisers the means to attack masses of unsuspecting people who otherwise avoid or are suspicious of less popular sites. The compromise is almost always immediate and invisible to victims and admins.

Much of it takes place when legitimate websites, often those carrying news or featuring pornography, load a third-party banner that an attacker has bought through an ad network or exchange. That ad contains some malcode that redirects visitors who receive it to a malicious landing page that executes various exploits tailored to the user's system. It establishes a beachhead through which payloads like bank trojans, bots, and ransomware are pushed.

The ad machine also offers easy access for criminals, who, thanks to the fast-moving nature of the advertising machine, appear indistinguishable from legitimate customers. In this marketplace, attackers reside in the lawless bottom tier where traffic, or inventory, is sold and re-sold off to buyers wanting to post their ads.

Moreover, the malvertising can be targeted to specific victims using the same features that legitimate advertisers use to hit users interested in the kinds of products they sell. This means criminals can target government IT shops looking for extended Windows support, or defence contractors seeking state tenders.

This buying and selling happens in real-time advertising exchanges, where anyone with the cash can pay to play. Once an attacker buys an advertisement, their artwork can be served to targeted users on specific websites as part of the deal. An attacker's ads may contain malicious redirects, exploit kits, or Adobe Flash exploits at the point of sale – or it may be introduced later.

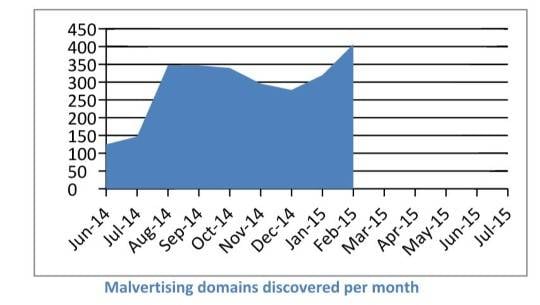

"Malvertising can be hard to measure because so many attacks go undetected," says Jerome Segura (@jeromesegura), senior security researcher at California-based MalwareBytes. "This is due to the fact that malicious actors are extremely agile and stealthy."

The malvertisements too are dynamic, meaning only some visitors to a site are exposed, which makes reproducing attacks difficult. Schultz says Flash advertisements are "basically miniature programs," meaning that the bad bits of an ad can be turned on once it is showing on a big-name site without triggering alarms, unless those analysing the artwork are really good at disassembling. Coupled with targeted advertising, attackers have "the ultimate flexibility in infecting who they want to infect and serving the exploit that matches a victim's system".

Poisoned ads are a natural progression for net villains in search of a means for mass distribution of payload, according to Nick Bilogorskiy (@belogor), security research director of California-based Cyphort. "Unlike worms' peer-to-peer viral approach, malvertising follows the one-to-many client-server approach, [where] attackers infect one advertising network and reach hundreds of websites that load ads from it, and millions of visitors to each of those websites," Bilogorskiy says. "And they don't even need to hijack or compromise the ad network – only need to buy an ad and obfuscate the malicious nature of the ad until it is reviewed by the ad censors."

Here hackers have many tricks to conceal their advertisements, according to the accomplished security boffin. These include enabling the malicious payload after a delay, serving the exploits to every fifth or so user, verifying user agent strings and IP addresses before delivering the exploit, and using SSL for redirection to frustrate efforts to follow attacker footsteps.

Credit: Cyphort.