This article is more than 1 year old

Bookworms' Weston mecca: The Oxford institution with a Swindon secret

The 400-year-old Uni library with a big-box backer

Triumphal avenue of eight million books

The BSF’s low-roofed processing hall is relatively quiet. This is where it accepts new items, sorts returned ones for refiling and readies items for the vans that take orders into Oxford twice a day, in the closable plastic crates often used for office moves.

Anyone ordering a book before 10.30am can get it delivered to the Bodleian reading room of their choice that afternoon; otherwise, it will arrive the next morning. The BSF sends out around 6,500 items in a busy term-time week, a total of 234,655 in 2014. Apart from the abstruse nature of the stock – a book in Polish, a set of essays on yoga – it looks like what it is: a warehouse’s processing section.

With a high-vis jacket, a member of BSF staff and a press officer, I progress through a roll-up metal door into Chamber 3, one of the four windowless rooms that hold the actual stock. And my sense of scale breaks.

I am facing a city of books, housed on metal shelving units, each more than two dozen shelves high. Each aisle looks like a triumphal Communist avenue in East Berlin – uniform and many storeys high – but with a road width from old Amsterdam. I am eye to eye with the fifth storey, but still feel dwarfed by the 11-metre-high shelves. Despite the sight of a distant far wall, the aisle appears to carry on over the horizon. Like the Grand Canyon, photos don’t really do it justice.

Aisle be seeing you: one of 31 passages of books. Photo: SA Mathieson

We walk down one of the BSF’s 31 aisles. The chamber is sealed, and quiet at the entrance; within the aisle, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of books, there is near silence. If we were to stay still long enough, the lights would go out as they are on a timer. The Bodleian’s press officer notices some curious two-foot long boxes on one of the eye-level shelves used to store items that don’t fit in the trays. So we open the box ...

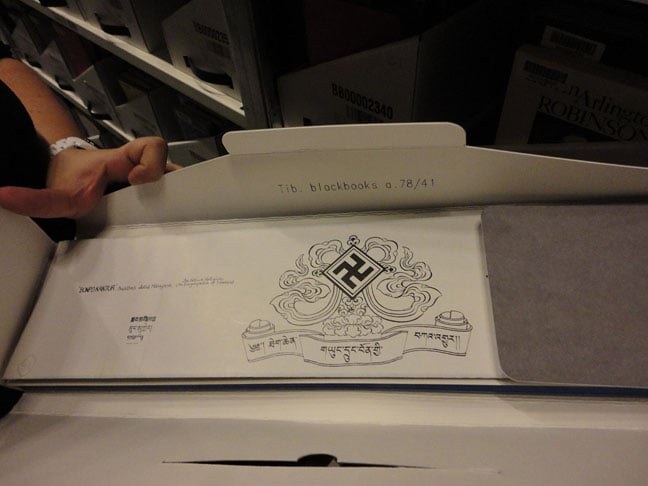

Of course, this is a Tibetan blockbook relating to that country's religious tradition of Bön. Note the clockwise swastika, symbolising the sun and the god Vishnu – the Nazis used the anticlockwise version. Still, you might find almost anything on these shelves; almost everything, in fact.

So how does it work? The trays were filled purely by size – otherwise, distribution is random, although there is a plan to move more popular material to the front of aisles. The BSF relies on barcodes, on every item on these shelves, every cardboard tray and every shelf location.

And the barcodes rely on the BSF Information System, provided by Generation Fifth Applications, a modified version of software used in equivalent warehouses run by Harvard, Princeton and Yale universities.

A Tibetan blockbook, among the sacred items filed and catalogued at BSF. Photo: SA Mathieson

“The one time we had a glitch with BSFIS, we had to down tools,” Boyd Rodger, storage and logistics manager for Bodleian Libraries, tells me. Adds Andrew Bonnie, chief of digital operations: “If we lose IT, people can’t find the resources, they can’t request them, they aren’t able to pick them. We’ve got them all safe and sound, but we can’t do a lot with them.”

BSFIS accepts incoming orders and works out an efficient route for staff to move along one side of an aisle and back along the other. Staff do not use really long ladders, but computerised forklift trucks from Jungheinrich, which owe something to Ripley’s warehouse suit in Aliens.

Potential recruits are taken up to the heights as part of their interview, to see if it puts them off. When working, they average one book a minute. Guides in the aisles stop the forklifts from hitting the shelves; computerised control was considered, but as humans would still be needed to pick and replace books, it was decided they might as well drive the trucks too.

The technology doesn’t end there. A building management system keeps the BSF at 17.5 Celsius, plus or minus one degree, and 52 per cent humidity, plus or minus five percentage points, the ideal levels to preserve paper.

Systems sniff the air for fires – although dust sometimes triggers a false alarm. Fortunately, the 15,000 water sprinklers are individually set off only by high temperatures nearby; it is much easier to restore a drenched book than a burnt one.