This article is more than 1 year old

The BBC's Space: A short history of 21st Century indoor relief

Digital: the magic middle-class makework word

Indoor relief for the media classes: a brief history

Space has echoes of the Nathan Barley quango, memorably described by readers as “Welfare for Wankers” – albeit on a much less grand scale.

Back in the pre-recession New Labour era, around 2007, Ofcom wanted to expand its empire and create a taxpayer-funded commissioner of new media stuff, called the Public Service Publisher, or PSP. Ofcom had found (to nobody’s surprise) a dearth of “public sector content” on the internet. A mere £100m a year would do the trick, and fix this most pressing problem – surely by now on a par with migration, climate change or famine. Parliament later quashed the idea.

Space’s interim CEO is Anthony Lilley, one of the prime movers behind the PSP, who we interviewed here back in March 2007.

Around the same time as the PSP was being spawned, Channel 4 hired BBC tech worthy Tom Loosemore to head up a new media fund, 4IP. Like the PSP, 4IP vowed to “reinvent public service media for the digital age”. The ideas funded were remarkably similar too, including “a discussion tool... [a] question and platform, which allows the public to put their concerns to ministers and high-profile figures” – as if Twitter and email had never been invented. Three years and £50m later, 4IP was dissolved. Loosemore resurfaced at the Government Digital Service as its deputy director, where, amid staff allegations of nepotism and cabals, he was in a key position as the credibility of HM Government’s electronic publishing operation disappeared down the toilet, only to quit in the great stampede for the exit last August.

The PSP idea was revived last year by former No 10 SPAD Rohan Silva, who identified (once again) a “chronic funding gap in the UK for companies creating digital media content, as our venture capital funds do not typically invest in this sector”. But for once, a gravy train had rolled out of the station without Silva on board. He hadn't been paying attention: one was merrily commissioning away.

These ideas were conceived in happy, pre-austerity days. The concept had been snuffed out by Ofcom and Channel 4, but had taken root at the BBC, where austerity only ever happens to other people.

We must build... a giant digital trough

Writing at the BBC in 2007, new media luvvie Bill Thompson*** argued that although everybody appeared to be sharing digital media everywhere you looked, this was actually an illusion. The taxpayer needed to be tapped up once again. Why?

“The real problem with MySpace, YouTube and Flickr and the many other social spaces, sharing tools and online collaborative mechanisms is not that they are privately owned, it is that there is no public service ethos behind them.”

Undoubtedly so, but did anyone other than Thompson and a handful of new media freelancers actually care? Undeterred, he outlined a grandiose vision. There would be a new er, something: “This does not have to mean a state-owned online social network, although it could do,” Thompson mused, before setting his ambitions a little lower.

Thompson was hired by his friend and former Guardian digital boss Tony Ageh, who was by now in charge of the BBC's incomparable archive, and a plan was hatched. Remember, this was before The Crash, a time when the BBC was burning through £120m outlay on its Digital Media Initiative, called by one the execs the BBC's "digital brain”.

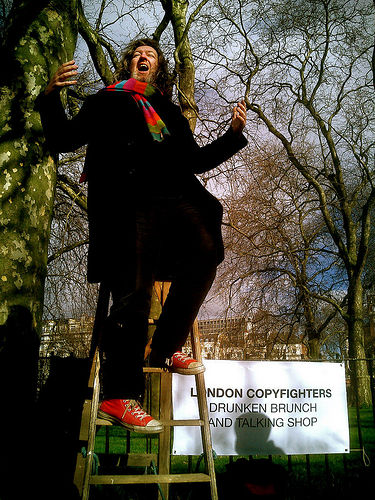

Bill Thompson. Pic: Cory Doctorow

Under the plan, the BBC would create a commissioning thing for digital media stuff, and so help save the internet. This is a classic expression of public sector narcissism, where the circular logic goes like this: Spending other people's money is what makes us virtuous. And we’re virtuous people, because we spend your money on things like this.

Ageh certainly showed signs of Noble Cause-itis when he described Space as a “higher calling for both the BBC and the Licence Fee”. Digital had become a kind of substitute religion; Minister Ageh and Minister Thompson were its evangelicals.

Yet the premise behind the plan was dubious and based on a fairly narrow and anti-humanist interpretation of developments in new media. When people complain about what’s wrong with the internet and what might make it better, it is unlikely that you will hear the words: “I simply can’t find anywhere to host or share my stuff. If only someone could start a photo-sharing social network!”

Sharing your photos on Flickr is not some underground samizdat activity. Digital media is characterised not by scarcity, but by ubiquity. As we’ve seen from time to time, what gets users riled isn’t the absence of a place to share stuff, but the terms on which individuals are required to share that stuff – and what’s subsequently done with that stuff. What’s under threat today isn’t some collective "space", but the gradual disenfranchisement of the individual from participating fully and exercising their legal and human rights on networks: specifically, the individual’s ability to own or control and maybe even trade their digital stuff.