This article is more than 1 year old

'Disruptive Innovation'? Take this theory and stuff it: MIT Profs

The inexorable rise of Silicon Valley's unchallengeable mantra

Comment "Disruption" – Silicon Valley's favourite buzzword for intimidating other, profit-making parts of the economy – has taken a knock.

Founder Clayton Christensen, a Harvard business Prof, spawned a consultancy and investment company off the back of his 1998 business bestseller, The Innovator's Dilemma. The buzzwords "disruptive innovation" and a cult followed.

Christensen posited that managers are too busy taking care of business as usual, or "doing the right thing", to notice and respond effectively to competitive change brought about by new technology. Companies often have the capacity to respond, but don't. The Harvard man took disk drive maker Seagate as his main example and took it from there. But the Christensen theory is deeply flawed, even by his own elusive and shape-shifting definition.

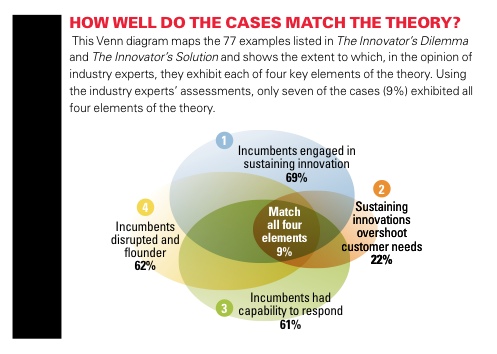

Andrew King and Baljir Baatartogtokh at MIT surveyed 77 "disruptive innovations" – mirroring the 75 in Christensen's follow-up book – and over 100 experts Christensen cited as disruption gurus.

Some examples Christensen cited as examples of "disruption" by new innovation plainly didn't fit his own disruption theory. He cited local slaughterhouses being "disrupted" by the invention of refrigeration and rail, for example, but butchers weren't "on a path of innovation", as the MIT pair point out – and local slaughterhouses disappeared not because of new technology, but because of changes in wholesale demand (the Civil War) and gentrification. People weren't so keen on an abattoir at the end of their road any more. The US auto industry is rich with examples, while Bethlehem Steel failed not because of innovation but the loss of protectionist tariffs.

In two out of five cases, Christensen's examples didn't actually have the capacity to respond to change. An example is printers of yellow pages directories "disrupted" by Google. They couldn't all just go out and start their own search engine.

And in some of Christensen's specific predictions, the exact opposite to what he predicted has happened. He predicted ultrasound would "disrupt" medical imaging, but the opposite happened, with radiation imaging (cheaper MRI) relegating ultrasound to niches.

Interestingly, King and Baatartogtokh point out that companies that failed because of "disruption" were often failing already, but the flaws were glossed over.

The backlash against the mindless "disruptive innovation" mantra blossomed after a terrific and well-argued assault in the New Yorker on the theory last year by Jill Lepore, also a Harvard Prof – this time of history.

Lepore accused the theory of being historicism (a theory of history, like Marx's historical materialism) that was pretending not to be historicism. She also noted how the buzzword-ninja couldn't deal with reasoned criticism: "Disruptors ridicule doubters by charging them with fogyism, as if to criticise a theory of change were identical to decrying change; and partly because, in its modern usage, innovation is the idea of progress jammed into a criticism-proof jack-in-the-box."

Christenen's specific examples weren't very good, she argued. Seagate has actually survived and flourished, Lepore pointed out – it's still with us. And when we last looked, it had lots of ideas about how to remain competitive with flash memory.

Christensen didn't care much for Lepore's roughing up, telling Bloomberg:

It wasn’t until a piece that we published in 2002 that we figured out the causal mechanism that is fundamental to the theory of disruption. It was a professor at Tuck, and he built a mathematical model and showed mathematically that I had gotten the causal mechanism wrong.

But that obviously just makes his theory more right, rather than wrong.

So does it discredit the theory? No, it just keeps improving.

King and Baatartogtokh's piece is a cheap (about £4) and informative read, while Lee Vinsel has a nice free summary here.®