This article is more than 1 year old

Thousands of 'directly hackable' hospital devices exposed online

Hackers make 55,416 logins to MRIs, defibrillator honeypots

Derbycon Thousands of critical medical systems – including Magnetic Resonance Imaging machines and nuclear medicine devices – that are vulnerable to attack have been found exposed online.

Security researchers Scott Erven and Mark Collao found, for one example, a "very large" unnamed US healthcare organization exposing more than 68,000 medical systems. That US org has some 12,000 staff and 3,000 physicians.

Exposed were 21 anaesthesia, 488 cardiology, 67 nuclear medical, and 133 infusion systems, 31 pacemakers, 97 MRI scanners, and 323 picture archiving and communications gear.

The healthcare org was merely one of "thousands" with equipment discoverable through Shodan, a search engine for things on the public internet.

Erven, an associate director at Protiviti and who has five years of experience specifically securing medical devices, said critical hospital machinery is at the fingertips of miscreants.

"Once we start changing [Shodan search terms] to target speciality clinics like radiology or podiatry or paediatrics, we ended up with thousands with misconfiguration and direct attack vectors," Erven said.

"Not only could your data get stolen but there are profound impacts to patient privacy."

Collao, of security consultancy NeoHapsis, said exposed networking gear and admin computers let attackers build up detailed intelligence on healthcare orgs, including the floors in which certain medical devices are housed.

"You can easily craft an email and send it to the guy who has access to that [medical] device with a payload that will run on the (medical) machine," Collao said.

"[Medical devices] are all running Windows XP or XP service pack two … and probably don't have antivirus because they are critical systems."

Executing custom payloads, establishing shells, and lateral pivoting within a network, are all possible, he said.

Erven ran through dozens of vulnerabilities that he reported in the last 12 months to big-name medical device manufacturers. These holes can grant scumbags remote administrative access to critical medical devices and supporting systems.

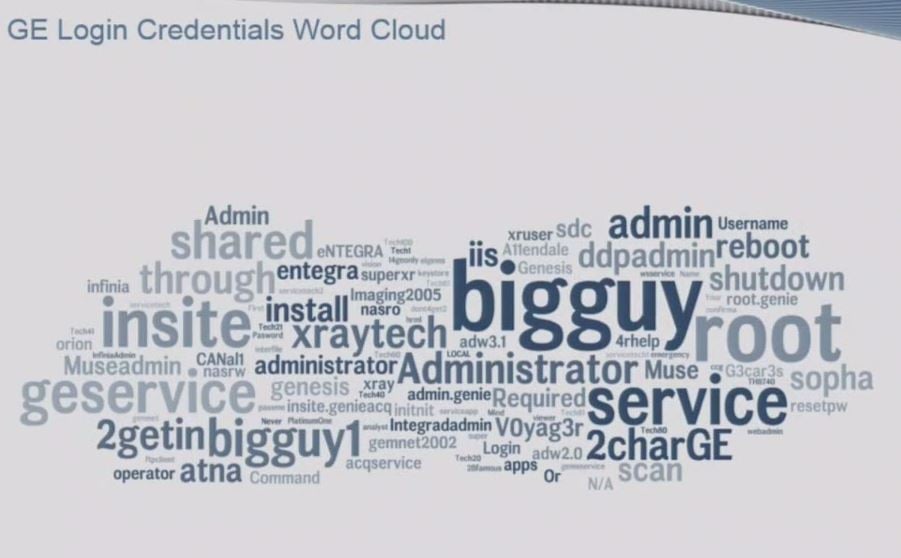

These most common GE medical device passwords grant login access 85 percent of the time, Erven says.

That included 30 holes in GE medical kit, which were reported this year and all rated a maximum severity of 10. Some enabled remote root access over Telnet and FTP to nuclear imaging and cardiology systems. Others had hard-coded or no password, including a popular default password "bigguy".

Patched flaws on older kit resurfaced in new machines, indicating a failure by manufacturers to fully scrub out bugs from products that can take years to change due to slow time-to-market. He listed credentials for more than 100 medical devices.

Erven said GE is one of the most progressive medical manufacturers in terms of dealing with bug fixes and interaction with the security community.

Proven attacks

The security men showcased the real-world risks to exposed hospital equipment after their "real life" MRI and defibrillator machine honeypots attracted tens of thousands of login attempts from miscreants on the internet.

In total, the machines built to mimic actual equipment attracted a whopping 55,416 successful SSH and web logins and some 299 malware payloads.

Attackers also popped the devices with 24 successful exploits of MS08-067, the remote code execution hole tapped by the ancient Conficker worm.

Collao said attackers did not appear to realize the machines they popped were would-be critical medical devices.

"They come in, do some enumeration, drop a payload for persistence and connect to a command and control server," Collao said.

"We can deduct that there is owned medical devices calling back to a C2 (command and control server) and that there is an attacker out there who does not know what they sitting on.

"These devices are getting owned repeatedly now that more hospitals are WiFi-enabled and no longer support arcane protocols."

The honeypots ran for about six months and mimicked devices "to a tee" complete with security vulnerabilities. The pair used Shodan to find devices on which to base their honeypots.

The pair also posted fake hacking data and medical device credentials to Pastebin and used a bogus Twitter hacker account to alert potential attackers that are interested in the space. ®