This article is more than 1 year old

Penetration tech: BAE Systems' new ammo for Our Boys and Girls

Military kit firm's Radway Green factory tweaks its bullet designs

Interview BAE Systems is, for the first time in many years, offering new types of small arms ammunition to the armed forces. It all boils down to achieving better penetration and pleasing the customer.

Famous as the home of British military ammunition production since its 20th century days as a state-owned Royal Ordnance Factory, Radway Green – better known as RG – recently announced it was supplying two new types of 5.56mm and 7.62mm ammo to the military.

What's changed? While your first thought might be that in this day and age it's something to do with lasers, micro-computers or new targeting tech, the answer is much simpler.

It's all down to penetration – or punching the same depth of hole in ever-better-protected targets.

While RG's existing products, the 7.62mm L44A1 and the 5.56mm L17A2 cartridges, did that more than well enough when they were originally specified by the Ministry of Defence, modern battlefield technology and techniques mean the military are looking for something with a bit more oompf to fire down their rifles and machine guns.

RG has swapped all-lead bullets for steel in pursuit of better penetration against hard targets – though there's a lot more to it below the surface.

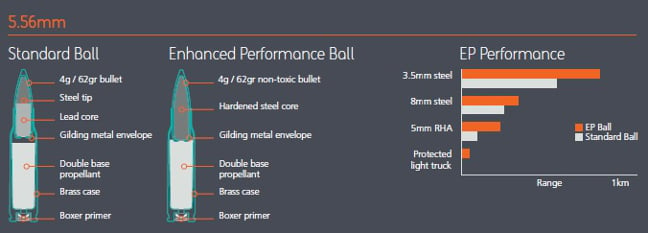

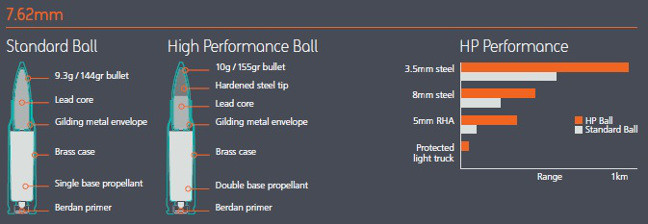

The two new designs of cartridge, known as the Enhanced Performance (EP) round in 5.56mm and the High Performance (HP) round in 7.62mm, feature new – and, in the HP's case, heavier – bullets. In addition, the HP round switches from single-base propellant powder to double-base, to give the heavier bullet the same flight characteristics as the old one. The EP also discards the age-old NATO SS109 bullet design, which incorporates a steel tip in front of a lead core, for an all-steel bullet, cased in the same gilding metal jacket as before. Its profile is similar, though.

BAE Systems' new 5.56mm Enhanced Performance round, also known as the L31A1

The biggest change for the 5.56mm round is the switch from a two-part bullet, made up originally of a steel tip and a lead core, to an all-steel bullet. While it continues to have a gilding metal jacket (an alloy of 95 per cent copper and five per cent zinc), the departure from the standard SS109 bullet design is relatively radical.

Simon Parker, a project manager at BAE Systems Radway Green, spoke to The Register about the new rounds and the decisions behind the changes in their makeup.

“We wanted to see if we could improve performance against hardened targets. Having a solid hardened steel core improves performance above that of the steel tipped round,” he said. The new 5.56mm round, which will be known as the L31A1 in British service, retains a bullet weight of 62 grains (4g), meaning its ballistic performance will be very similar – an important similarity for soldiers firing it down their SA80 rifles.

Seven point six two millimetre full metal jacket

For the 7.62mm round, known as the L59A1 in British service, the biggest change is to the weight of the bullet, from 144 grains (9.3g) to 155gr (10g). This increased maximum weight allows the new bullet to incorporate a steel tip, similar to the 5.56mm NATO SS109 design, giving it more mass with which to punch through a light target. Graphs from BAE claim that the HP bullet can penetrate an 8mm steel sheet out to about 400m, whereas its predecessor could only manage it at half that distance.

“We have a standard ball round which is 144gr and a sniper round which is 155gr. The sniper round is manufactured under tighter tolerances and conditions. The 7.62mm High Performance round is not quite the same as the sniper [round] but it's considerably improved over the standard 144gr bullet,” said Parker.

The propellant in the new 7.62mm round is the same as the 155gr L42A3 sniper rifle round, which is continuing in production. It is a double base propellant – so why the change from single base?

“It's merely because it's heavier,” said Parker. “Moving from the 144gr to the 155gr means you need a bit more energy in the propellant. We already use the double base propellant in the sniper round so it's the same propellant as is used in the sniper round.”

The 7.62mm High Performance Ball round, aka the L59A1

“We're focused on improving performance for the customer and end user,” continued Parker, emphasising the new rounds' penetration characteristics. “Having a bit of additional weight [in the bullet] helps because it increases the energy that you're carrying to the target. Putting the hardened steel tip in is part of that. Having the higher weight improves the consistency and accuracy of the round as well.”

How does it perform in real world terms – and is it just RG's famous Green Spot sniper ammunition, last seen in the 1990s, under a new label?

“The old Green Spot was just the best lot of ammunition that we manufactured, taken off and marked as Green Spot... but 7.62mm HP would outperform Green Spot,” said Parker.

“We've not designed it for a sniper rifle application – though the Special Forces use it as such and that's fine – but it has been adopted in the sharpshooter rifle [the Army's L129A1]. It was purchased as a UOR and subsequently adopted. We recommended the use of 7.62mm HP and the user really loves it. But it was originally designed, truth be told, for improved target performance through any weapon system. We made it and designed it so it can be functioned through the GPMG and it's also being used by the Royal Navy in their Miniguns for defence of ships.”

Boats, tails, and ballistics

The all-steel core bullet on the new 7.62mm round is ever so slightly longer than its predecessor. “Because of the way the design has lengthened the bullet, there's a greater overall length so through a rifle you get better consistency,” said Parker. Though he would not reveal precise specifications of the new bullet, which is a proprietary BAE Systems design, he did confirm it continues to feature a boat tail, as well as the customary gilding metal jacket.

Boat tail bullets are so named because the rear end is coned off rather than being left as a cylinder, looking in cross-section a bit like a boat. More information is available here.

For the real tech spec enthusiasts, what's the new bullet's ballistic coefficient?

“All our modelling and our work relates around drag coefficient,” said Parker. “With modern computational fluid dynamics programs that's all you need. The old ballistic coefficient is the shooter's way of doing things. The Special Forces and the army tend to use it in their lookup tables but we don't tend to use them very much.”

In other words, that's on a need-to-know basis. In the catalogue image (featured above) the bullet profile looks entirely conventional, with the core exposed in the base, so civilian target shooters and hunters might expect it to be in the 0.3-0.4 region.

Not, however, that they'll be getting their hands on these rounds. BAE Systems company policy is that it does not sell to civilian end-users. A company PR rep confirmed to The Register that this is purely company policy and not down to any external treaties or agreements.

Shake, rattle 'n' roll, baby

No matter how funky the new ammo might be, it still has to pass the Ministry of Defence's rigorous pre-service tests. These determine not only whether the ammunition is safe to use, but whether it is still safe to use after being subjected to the harsh conditions of military life.

“We cook [the rounds] in ovens for weeks on end and it cycles up and down so we simulate up to 212 days, diurnal cycles, the daily extremes,” Parker told El Reg. “It goes up to 71 degrees (Celsius) and down to -54 degrees. We then have to go through 'shake, rattle and roll' which simulates the environment from manufacture through to final use. That would include air transport – Hercules C-130, all those sorts of things – and then tactical transportation, so we would then simulate Warrior [armoured fighting vehicle] vibration, attack helicopters, you name it.”

The ammunition must be able to survive these extremes and still function reliably within normal parameters. If it doesn't, the whole batch – tens of thousands of rounds – may be rejected.

The exact tests “can be a mix of defence standards and other things that will tell you the environment it needs to be subjected to,” Parker told us. “Sometimes we use a generic one and that will say 'a generic aircraft vibration spectrum for propeller aircraft is this' and we'll subject it to that.”

“In other instances it's very specific to platform and it can be very different from the generic ones,” he said. “The customer will say 'you've got to subject it to this'. For example... there is a very specific vibration spectrum associated with the Warrior armoured vehicle. We would do that in whatever pattern configuration it would see in that platform.”

“The early transport stuff could be palletised. In the Warrior it'll be in H83 boxes that simulate it being thrown into the back of the vehicle. Some of them are individual rounds [to simulate one that might have been] dropped, and things like that, and exposure to temperature [tests] can be on individual rounds or links or belted links. It is a very costly and time-consuming activity but one that is arguably necessary to ensure the safety and suitability of the product.”

Is all of this strictly necessary? Parker is firmly on the side of "yes":

“It's subjected to an enormous amount of testing to prove that it does meet all those requirements. I don't think Mr Apple does that all the time – hence if you drop your phone it tends to break – whereas with our stuff it has to meet the standard.”

Going green

Environmental friendliness is also a surprising but very real concern for the ammunition industry. Lead fired into watercourses and wetlands can slowly contaminate fresh water sources and poison aquatic life – rather than being a health hazard for the intended recipient.

Was BAE Systems' move to a steel bullet core for the 5.56mm EP round inspired by moves to go green?

“Having that non-toxic bullet is a potential way forward and we're also looking at switching to non-toxic primers. As it stands, the round that we would see going into service would have a standard lead styphnate primer because it would provide the approved performance,” Parker told us, adding: “We recognise there may be a demand to move to non-toxic, lead-free ammunition and therefore you need to do two things: take the lead out of the bullet and the lead salts out of the primer. We're pursuing this as a separate strand from the EP round.”

The other technological innovation RG is pursuing is a full factory overhaul, with BAE Systems spending £84m overhauling its small arms production lines.

“That's for production of cartridge cases and bullets, and assembly of all the natures of ammunition including ball rounds, tracer rounds, blank ammunition... and all the packing machines and linking. We have a facility that was last updated in the 1980s with the introduction of 5.56mm and that was really the last investment,” Parker said of the RG production line.

“We were replacing some of the machines on an ongoing basis,” he continued, “but the facility hasn't changed. So what we did was basically built a brand new facility which was then populated with new machines, refurbished machinery and some of the newer machines from the old facility. They have all been interlinked so that rather than being stand-alone processing machines which required manual carrying of product out of one machine and loading it into another, there's a reduced labour force requirement, hence the whole thing is much more cost-efficient and effective.”

On a two shift production cycle, RG is capable of producing 240 million rounds of ammunition a year. Those sort of volumes might put even Apple's volume production to shame. ®