This article is more than 1 year old

We want GCHQ-style spy powers to hack cybercrims, say police

Why catch crooks when you can DDoS them from the nick?

Traditional law enforcement techniques are incapable of tackling the rise of cybercrime, according to a panel of experts gathered to discuss the issue at the Chartered Institute of IT.

Last night more than a hundred IT professionals and academics, including representatives of the National Crime Agency and Sir David Omand, the former director of GCHQ, discussed what they saw as the necessity of the police acting more like intelligence agencies and “disrupting” cybercriminals where other methods of law enforcement failed.

The perpetrators of cybercrime are often not only overseas, but in hard-to-reach jurisdictions. Evgeniy Bogachev, the Russian national who created the GameOver Zeus trojan, for instance, currently has a $3m bounty on his capture – but Russia does not want to hand him over to the US.

In such situations, when arrests are not possible, disrupting criminal activities “may be the only response” suggested Sir David Omand, adding that “the experts in disruption are in the intelligence community.”

Technical disruption, as the NCA practices it, can involve sinkholing, getting hold of the domains used by malware to communicate and so breaking its command and control network. Paul Edmunds, the head of technology at the NCA’s National Cyber Crime Unit, explained how Operation Bluebonnet took aim at the Dridex banking trojan, but said that sinkholing it and organising arrests required a concerted international effort – one that may need to be repeated with the “up-and-coming” exploit kit Rig.

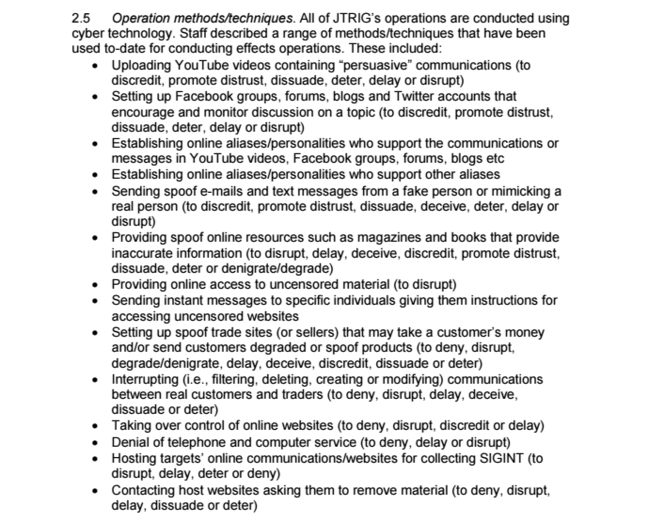

Disruption as an intelligence agency technique, however, is a much more proactive and engaged activity. A Snowden-provided document covering the activities of GCHQ’s Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG) showed active “disruption” targeted at those flogging malware. The attacks included providing false resources and denial of service attacks.

Six users of the Lizard Stresser DDoS-for-hire tool were arrested by the NCA last year – when the agency’s average age for arrests dropped from 24 to 17 – and the agency was surprised when it discovered its users were all very young and male, as NCA officer Zulfikar Moledina explained to those attending.

When the NCA tackled the use of the Blackshades remote access trojan last year, it had 750 suspects who had used it. It sent 350 emails warning downloaders, 200 “influence letters”, and 99 cease and desist notifications. 21 individuals were arrested; among those who bought the RAT was a 12-year-old boy.

In response to this demographic shift, the NCA launched a “Prevent” campaign last year – sharing a name, if not policy, with the controversial counter-extremist strategy – targeting the parents of 12-15 year old boys whose web hi-jinks could potentially progress towards serious cybercrime.

Disrupting real offenders and providing guidance to potential offenders – encouraging them to engage in more productive activities – must be part of a more considered response to cybercrime, the panel considered.

Professor Gloria Laycock OBE, the founding director of the Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science at UCL, explained the model for dealing with meatspace crime and how that could be applied to cybercrime.

According to an attrition table on crime rates published by the Home Office, for every 100 crimes committed only 50 are reported to police, even fewer of those reports are recorded and a mere two per cent of crimes are successfully prosecuted.

Laycock said that while a means of punishment and retribution is necessary, this showed that “you cannot control crime through the criminal justice system.”

Instead, there are five ways to reduce crime: increase the effort criminals need to apply to commit the crime successfully; increase the risks criminals need to take; reduce the rewards of criminal activity; remove the excuses for it; and reduce provocation.

When it comes to cybercrime, the questions that persisted were whether it could be designed out of the systems we use, and if not whether it was possible to better educate the public. To what extent police need the security and intelligence agencies' powers to deal with cybercrime was a strongly recurring theme as well. ®