This article is more than 1 year old

Uber's self-driving cars can't handle bike lanes, forcing drivers to kill autonomous mode

Hmm.. our software breaks the law? Ah, well, just ship it

Uber's claim that its self-driving cars don't qualify as self-driving cars, a stance challenged on Friday by California Attorney General Kamala Harris, becomes more complicated in light of findings that the vehicles, while under software control, can't follow the law when it comes to cyclists.

In an article published on Thursday, Brian Weidenmeier, executive director of San Francisco Bicycle Coalition (SFBC), warned that autonomous Uber vehicles fail to drive legally when turning across bike lanes. Uber just started experimenting with self-driving rides in the city.

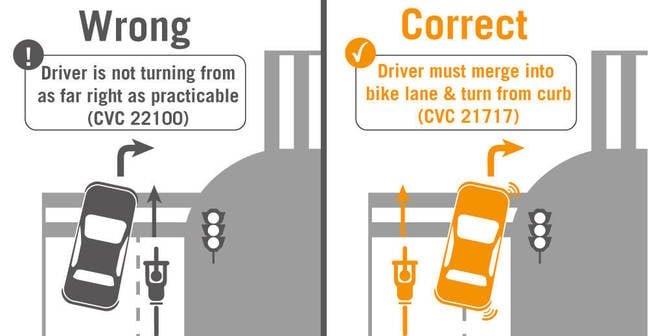

The law requires that vehicles merge into a right-hand bike lane before making a right-hand turn, while yielding to any cyclist who happens to be there at the time.

But Uber's not-quite-self-driving cars don't do that, according to the SFBC, which says the vehicles make unsafe turns from the car lane, endangering cyclists in the process.

"On my colleague's brief demo of an autonomous vehicle last Monday," said SFBC communications director Chris Cassidy in an email to The Register, "the vehicle twice made an illegal and unsafe right-hook-style turn through bike lanes."

Cassidy said that while he wasn't aware of how many incidents like this have occurred with Uber vehicles, the behavior has also been observed in accounts posted through social media.

Right from wrong ... How you're supposed to take the corner in America (Source: SFbike.org)

Cassidy noted Uber was informed of the issue and then, two days later, began testing its not-really-self-driving cars on San Francisco streets, before any fix could be made.

"The potential for autonomous vehicle technology is exciting, but knowingly rolling out unpermitted, unsafe vehicles shows a blatant disregard for people's safety," said Cassidy.

In an email to The Register, an Uber spokesperson confirmed that its vehicle operators "have been instructed to disengage from self-driving mode when approaching right turns on a street with a bike lane and that engineers are continuing to work on the problem."

In a blog post last week, Uber said that riders requesting an UberX in San Francisco will be matched with a "Self-Driving Uber" – as Uber defines the term – if one is available, and that the company believes it does not need a permit to test autonomous vehicles because its vehicles aren't autonomous.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) disagreed and directed the company to comply.

In response, Uber held a press conference call on Friday in which Anthony Levandowski, head of Uber's advanced technology group, said the company disagreed with the DMV's assessment. In prepared remarks, Levandowski reiterated the claim that self-driving does not mean autonomous, as defined under the law.

"[T]he Self-Driving Ubers that we have in both San Francisco and Pittsburgh today are not capable of driving 'without ... active physical control or monitoring'," he said, likening the technology to assistive driving technology like Tesla Autopilot.

Cassidy expressed skepticism of Uber's reasoning. "Uber's argument that their autonomous vehicles are not actually autonomous is convenient, but flies in the face of common sense and legal statements issued by the California Department of Motor Vehicles and the California Attorney General," he said.

Indeed, the California Attorney General sent Uber a letter on Friday directing the company to immediately remove its self-driving cars from the roads until they're properly permitted.

automated uber lined up for turn in right-hook lane. at least its turn signal is partially on. attn: @sfbike @CA_DMV @sfmta_muni pic.twitter.com/gnJFkWvYlU

— @wednesdaynight✌️ (@wednesdaynight) December 16, 2016

The Register asked the California DMV, the Office of the California Attorney General, and Uber about the state of the standoff on Monday, but didn't receive immediate answers.

Uber's claim that its technology doesn't qualify as automation looks difficult to sustain in light of the definition provided by SAE International, an automotive professional organization. The firm's six-level rating system suggests self-driving Ubers would fall under SAE Level 3, Conditional Automation, which entails a human operator who can disengage automated acceleration, steering, and braking systems.

The Register asked SAE to weigh in on the matter but hasn't yet heard back.

A San Francisco city official knowledgeable about the matter expects that Uber will seek a permit in January, to avoid having to provide 2016 data to state regulators. The official, who in a discussion with The Register asked not to be named, said Otto, a self-driving truck maker recently bought by Uber, has been testing on California roads without a permit for several months.

Otto last year reportedly flouted Nevada's permit requirement for autonomous vehicles.

A spokesperson for Otto confirmed in an email to The Register that the company has been testing self-driving trucks on state roads without an autonomous vehicle permit. "Otto has been driving its vehicles in California," the spokesperson said. "A vehicle operator is always in control of the Otto trucks while the tech provides driver-assist functionality."

Uber's reflexive resistance to regulation makes sense, given Silicon Valley's assumption that rules apply only to everyone else. But the company appears not to recognize that some regulators share its ostensible ambition to improve transportation.

The San Francisco official expressed support for forward-looking approaches to transportation like ride sharing, and frustration with Uber's unwillingness to engage in a productive manner with state and local representatives. "We're running out of room in San Francisco," the person said. "We can't have the Wild West any more." ®