This article is more than 1 year old

As ad boycott picks up pace, Google knows it doesn't have to worry

Why the agencies will come crawling back

Analysis Several US-based advertisers have now suspended their advertising with YouTube, following over 200 pull-outs in the UK and Europe. Google had run big brand advertising on hate videos including jihadist groups. Johnson & Johnson, Verizon, AT&T are the latest to hit pause, or withdraw ad budgets from YouTube altogether. AT&T is one of the top-five advertisers in the US, the New York Times notes. In 2015 it was the third biggest spender with $3.3bn across all media, according to AdAge.

Google has said sorry, and promised to conjure up a few new tools. What Google hasn't said, and what it hasn't promised, is far more revealing.

There will be no refunds for brands that have been defrauded. That money is in Google's coffers, and if you're a brand or an agency, you can consider it spent. More significantly, nor has Google committed to greater scrutiny or judgement over the material it distributes and monetises. This is what Google UK and Ireland MD Ronan Harris wrote on Friday, before the infection became a contagion.

Note the emphasis on providing tools for advertisers to make the choices ("simpler, more robust ways to stop their ads from showing against controversial content"), rather than Google increasing resources or editorial control. Google's Europe boss Matt Brittin echoed this line on Monday: advertisers were to blame for not using the tools that Google so thoughtfully provided.

The Times' reports about big brand ads running over content that breaches YouTube guidelines had been simmering for over a month when Harris blamed the advertising industry for other woes: lack of transparency. They weren't "educated" enough. Google also says it's drowning in video being uploaded to the site, and it's only human. Or robot.

One or two of counterfactuals are needed to put this in perspective.

In reaction to the YouTube ad boycott, Alphabet chairman Eric Schmidt described it as "essentially a ranking problem. We're very good at detecting what's the most relevant and what's the least relevant. It should be possible for computers to detect malicious, misleading and incorrect information and essentially have you not see it."

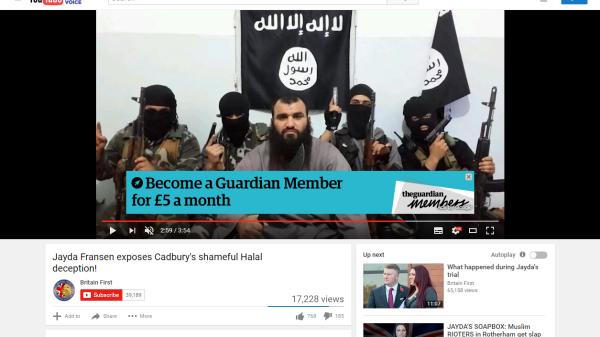

Yes, it should be, you'd think. Take the much-cited example below from The Times. Does anything in the image suggest it could be a jihadi group?

Perhaps not at first glance. But look closely. Any clues?

Almost every day Google touts some breakthrough in pattern matching, thanks to its PhDs and vast computing power. These are apparently miraculous. But although content inciting violence clearly violates YouTube rules, an image of a jihadist group in balaclavas seems to evade it. Google shows much more vigour in mining your health records than it does checking uploaded material complies with its own rules.

For in some instances, the existence of hate material on YouTube isn't exactly a technical glitch, but a conscious decision. The Times today notes the example of Wagdi Ghoneim, an Egyptian-Qatari cleric banned from the entering the UK. Videos on Ghoneim's Wagdy0000 YouTube channel have been watched over 31 million times, with Google handing over an estimated $78,000 in ad revenue. The Wagdy0000 channel is no accident, as lawyer Chris Castle explains at the MusicTechPolicy blog, which has documented how big brand advertising on illegal content is monetised on YouTube for over five years.

If we follow the money as Google has suggested many, many times, it is clear that it is not possible to have a monetized YouTube channel without at least two layers of approval by Google. Google also knows who to pay, which bank account to pay, and presumably the taxpayer name and tax ID number for the account. And of course I would assume that Google would be sending an IRS Form 1099 to the channel partner or otherwise complying with taxing authorities. Following the money in this case would be very simple, particularly if Google is cooperating.

The Times notes today that, amazingly: "Although Google disabled advertising on Ghoneim's YouTube page for UK brands, it appears to have allowed US commercials to continue to play there."

But why would that be?

Only two years ago, Google's chief counsel was warning policy makers not to "censor" jihadi hate speech on YouTube, but instead regard it as a messaging opportunity for governments.

"We don't believe that censoring the existence of ISIS on Google, YouTube or social media will dampen their impact really," he said. "Technology is one of the greatest tools we have to reach at-risk youth all over the world and divert them from hate and radicalisation. We can only do that if we offer them alternatives. Only on open and diverse sites like YouTube... we can find these countervailing points of view."

Consider that statement alongside the pledge to give advertisers better tools, and the message to Google's advertising customers is: "Those video nasties are staying up. If you don't want to monetise it, then fine. We're sure someone else will."

Years ago an advertising transaction was fundamentally the same as it is today: a brand bought some popular media space. But media companies didn't own advertisers, and advertising agencies didn't own TV or print companies. The difference today is that Google and Facebook are the media – they're the dominant digital billboards where users spend their time. I, for one, will be amazed if the agencies or the brands decide they can stay away for very long, and perhaps that's what explains Google's business-as-usual response. Google knows that too.®