This article is more than 1 year old

Farewell Cassini! NASA's Saturnian spacecraft waves goodbye for its Grand Finale

But the mission is far from over, say scientists

Cassini, one of NASA’s flagship spacecraft, is poised to meet its fiery end today as it plunges down into Saturn’s atmosphere at a speed of 123,000kph (77,000mph) per hour, where it will soon vaporise.

The shuttle was to point its antennas in the direction of Earth as it sent its final message at 03:32 PDT (10:32 UTC), although the final bits of Cassini's signal will not reach Earth until nearly an hour and a half later, due to the travel time for its radio signal.

Cassini began its mission in space almost two decades ago when it was launched in October 1997, carrying the Huygens probe. Together both spacecraft made the seven-year journey to Saturn, the Solar System’s most complex and unique-looking planet.

Saturn is like a mini Solar System. Its 62 moons orbit the gas giant in nearly the same plane and direction as one another, like the planets circling the Sun.

The 13-year mission has provided scientists with a wealth of data. Alexander Hayes, an assistant physics professor at Cornell University, United States, studying Saturn’s moon, Titan, told The Register that the variety of science collected was “unparalleled” in his opinion.

All the giant planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, all have ring systems, but none are as magnificent as Saturn’s. Numerous rocky particles caked with dust and ice ranging in micrometers to several meters extend across the planet arranged in concentric circles stretching to 175,000 miles (282,000 km).

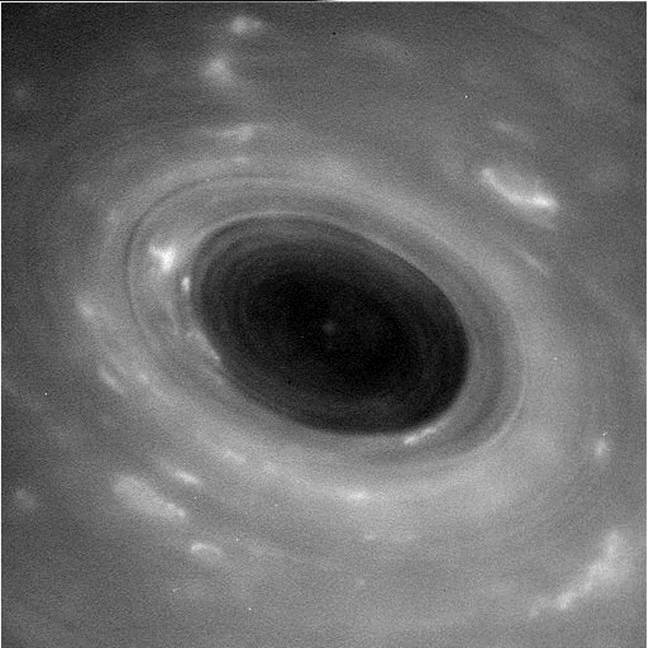

Close up of Saturn's rings.

Scientists have managed to study how the rings interact with Saturn over time, and how its moons gravitational effects shepherd the herds of rocks to keep the rings in shape. It’s a situation that is reminiscent of the early Solar System, where the Sun was surrounded by an accretion disk swirling with bits of dust and gas that eventually clumped together to form planets.

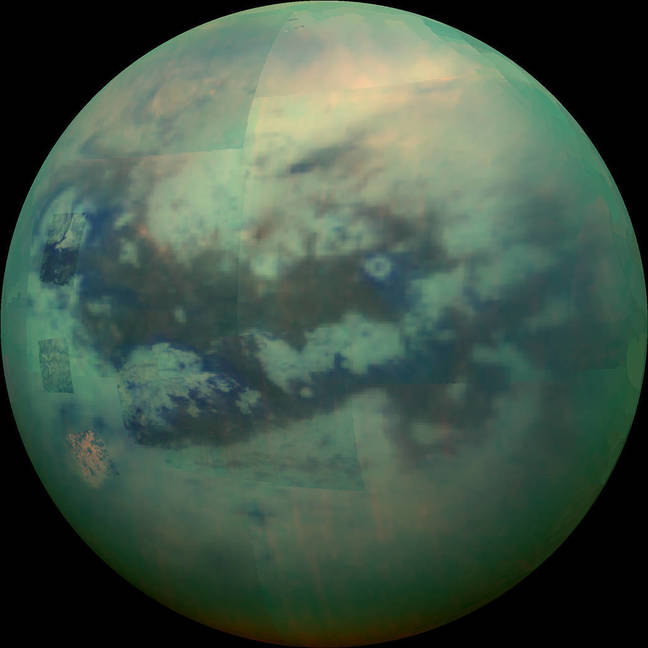

Cassini hasn’t just given scientists a chance to look back at the Solar System’s past, but also its future too. The discoveries of plumes of water vapour shooting out of Enceladus and a hazy atmosphere teeming with carbon compounds on Titan have led scientists to believe that both moons might harbour life or have the right conditions for life to bloom later on.

“We now know there is potential for a second genesis of life on Enceladus and Titan,” Hayes told The Register. “Both moons have a liquid oceans underneath their icy crusts. Titan is arguably the most Earth-like body. It’s one of the few places place to study prebiotic life. There is evidence of hydrothermal vents that exhibit a geological and chemical complexity like the deep sea geysers on Earth.”

Composite image of Titan taken by the Cassini orbiter.

Whilst Titan is mostly made up of nitrogen and methane, Enceladus contains more hydrogen and oxygen and contains liquid water - a key ingredient for life. It’s been chosen as a target alongside Jupiter’s moon Titan, for the James Webb Telescope which will search for signs of microbial life.

Cassini was born to die. NASA’s concerns that it could potentially collide with one of Saturn’s moons and potentially contaminating it means that the spacecraft has to be disposed of.

Although Cassini will be ploughing to its death and burning up in Saturn’s atmosphere, it’s not the end of the mission. “I came to California thinking that I was going to go to Cassini’s funeral service, but it’ll only be crocodile tears. Whilst the spacecraft is going to be disposed of, the science isn’t going to stop. I’m sad that there will be no new data, but there will still be new discoveries,” Hayes said. ®