This article is more than 1 year old

Why isn't digital fixing the productivity puzzle?

Paying people better matters just as much. Maybe more so

Analysis Oh dear. If all this new technology is so amazing, why isn’t it translating into productivity gains?

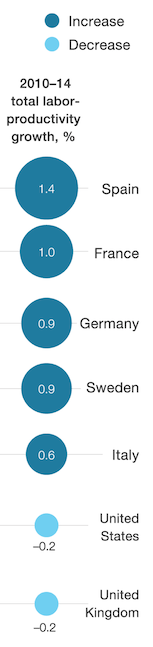

The question has been bothering economists and policy-makers for almost a decade. Since the 2008 financial crisis, productivity in many major Western economies has been flat. A hefty new examination by McKinsey’s eponymous think tank the MGI offers a few reasons why - and explains why "digital" doesn’t seem to be helping.

The authors of Solving The Productivity Puzzle: the Role of Demand and the Promise of Digitisation at the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) depart from the sunny forecasts typically made by “thinkfluencers” and tech hypesters. Digital should feed through into productivity gains, they say… but then again, it might not. Network effects create monopolies, and monopolies are usually anti-consumer. It’s a nuanced stance.

“Exceptionally weak productivity growth in recent years has raised alarms at a time when advanced economies depend on productivity growth more than ever to promote long-term economic growth and prosperity,” author Jaana Remes and her five colleagues write. “In an age of digital disruption, when companies are focused on implementing digital solutions and harnessing innovations such as automation and artificial intelligence, disappearing productivity growth is even more puzzling.”

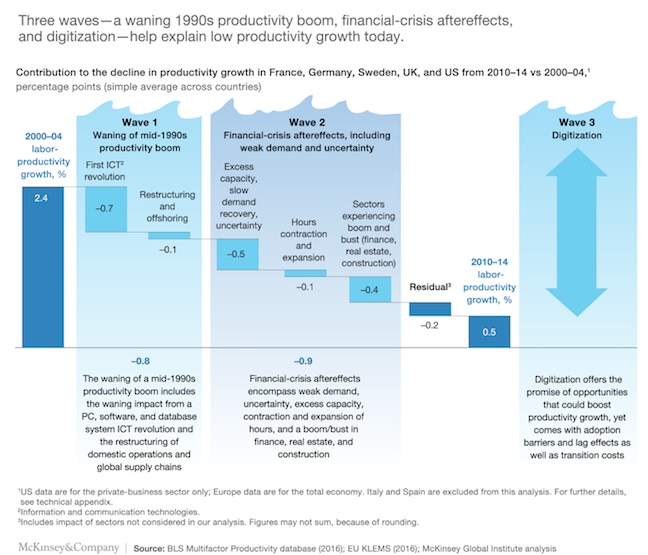

Productivity is defined as GDP output divided by the total of hours worked, and for years the PC boom helped drive increased productivity. Companies rejigged their supply chains. More databases were being used. This was the “first wave” and it began to wane around 2005: the productivity gains had by then had mostly been pocketed.

The second wave followed the financial crash of 2008, which saw investment slowdown. But the much-trumpeted third wave of digitisation hasn’t yielded “benefits at scale” yet.

Why could this be?

MGI suggests that transition costs are daunting and mean companies must cannibalise their existing business, making the case far from clear-cut. One example is in retail, where stores can shift more with fewer people online, but at the expense of their successful physical stores. “Transition costs can include an initial duplication of structures and investment, cannibalization of incumbent business, and the diversion of management attention,” the authors note.

Companies undertaking “digital transformations” say 17 per cent of the market share from core products was being cannibalised.

Spending power

Nonetheless 60 per cent of productivity gains over the next decade should come from digital. But should doesn’t mean will, and MGI rates this as a huge questionmark. Why?

In The English and Their History, Brit professor of French history Robert Tombs reminds us of one massive overlooked factor in why Britain had an industrial revolution. More people were relatively more prosperous than in Europe, and were able to buy more goods. It was a revolution of consumption and demand.

The French tried to will their own industrial revolution into existence. For example, the first coke-fired blast furnace iron plant was built at Le Creuset. “It soon became a white elephant,” Tombs writes. “Where wages were low and skills rare, expensive prestige projects failed.” While in England, “bouyant consumer demand ensured that new technology made profits”.

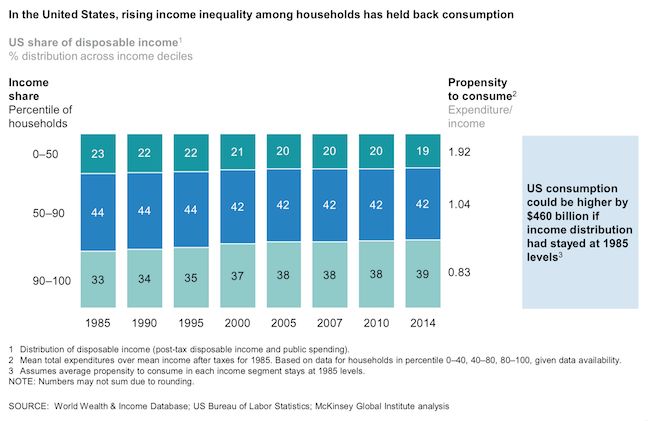

McKinsey doesn’t quote Tombs, but it does emphasise the importance of demand. Low wage growth has been a factor over the past decade and it will thwart productivity gains from digital.

“Slow wage growth dampened the need to substitute capital for labor,” the MGI team notes. “Low wage rates in retail in the United States, for example, seem consistent with comparatively slow investment in technologies like automated checkouts and redeploying freed-up resources in low-productivity occupations like greeters.

"In addition, stagnant wages had implications for limiting demand growth. In our sector analysis, we found weak demand dampened productivity growth through other channels than investment, such as economies of scale and a subsector mix shift.”

There are some non-obvious ones too. As the population gets older, it spends more on healthcare and services. Increasing the services part of your economy will slow productivity growth overall: something economists call Baumol’s cost disease.

Half of the answer, MGI suggests, comes from stimulating demand particularly of low-income consumers, “unlock private business and residential investment”, for example. To promote “digital diffusion”, policy makers should encourage better SME connectivity and infrastructure and digitise public services. That’s gone great so far.

An unequal society isn’t going to be a prosperous one. Keep that in mind the next time you hear someone make the case for the universal dole, advocated by tech oligarchs like Mark Zuckerberg. ®

The full report is here.