This article is more than 1 year old

Blueprint of modern construction can be found in a tech cluster... of 19th century England

The world's first iron-framed building will return to service soon

Geek's Guide to Britain The top of Flaxmill Maltings' Jubilee Tower makes you feel like you're standing on the highest turret of a massive castle built to command Shropshire. You can look down on suburbia and ahead to the centre of Shrewsbury, while in other directions the Wrekin is to the east and the Welsh hills are to the west.

But your eye will be drawn upwards. This tower, built in 1897, is topped by a vast metal crown to celebrate Queen Victoria's 60 years on the throne. Had the veteran monarch been the size of King Kong, it might have fitted her nicely. But celebrating a royal job anniversary seems secondary to focusing on the material used for it – iron.

You might expect to find the world's first iron-framed building in a big city, where land is at a premium – not an historic market town with a population a little over 70,000 and perhaps better known as the birthplace of renowned naturalist Charles Darwin.

But the world's great cities rely on this construction technique for offices, housing, bridges and monuments – imagine Manhattan without skyscrapers, Paris without the Eiffel Tower or Sydney without the opera house or harbour bridge.

But Flaxmill Maltings, named after its two historic industrial uses, built in 1796-7 and situated in a small county town near the edge of England, holds the crown.

Driving through Shrewsbury, it's hard to miss this big box of a building, surrounded by mostly empty land.

At the time of writing, its visual impact is reduced by much of it being covered in scaffolding; apart from a small, limited-opening visitor centre, Flaxmill Maltings is basically a building site.

Why?

This 220-year-old once-derelict landmark is midway through a seven-year £31m-plus renovation by Historic England to remove it from the heritage-at-risk register and open it to public and commercial use. So far, the work has deployed 30,000 handmade bricks and added six new load-bearing columns to just the mill's ground floor.

The mill at present (Photo: Copyright Historic England)

It will again dominate the town when it reopens as offices and a museum.

So how was it that Shrewsbury – not some burgeoning or bustling city – should become home to the world's first iron-frame building?

The answer lies in technology clustering. Nine decades earlier and 12 miles east-southeast, a man called Abraham Darby hired a furnace. He had worked for a company that made mills for crushing malted barley – a process involving coke derived from coal, used to dry the barley – then in a brass works that used sand moulds.

In 1707, Darby drew on his experience to patent a way to use sand moulds to make cast-iron pots. In 1709, he converted the Old Furnace in Coalbrookdale from running on charcoal, a fragile fuel that required carefully managed woodlands nearby, to coke. Coal could be mined and stored, making it much more reliable than anything fuelled by charcoal.

"It's the combination of using coke, along with his patent, that leads to success," Gillian Crumpton, director of collections and learning for the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, told me on my trip to the area for Geek's Guide. "He didn't come to change the world, he came to make money." But by kicking off iron mass production, change the world he did.

Darby and his successors made pots, wheels, rails, engine cylinders (eventually adapted for steam engines; the world's first railway locomotive was assembled here), fireplaces, statues, ornamental furniture and posh cookers (Coalbrookdale's AGA plant only closed in 2017). Their story is told well by the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron, located in what was the Coalbrookdale Company's Great Warehouse, a few hundred yards from the Old Furnace.

But the area's iron icon is the bridge that gives the gorge its name. Built by Abraham Darby III, partly because the steep sides of the River Severn could use a high bridge and also as a publicity stunt, the world's first iron-constructed bridge opened on New Year's Day 1781 at a total cost of more than £6,000, equivalent to around £1m today.

Unfortunately, Abraham III had estimated the bridge would cost £3,200 and the Coalbrookdale Company was plunged into debt. Furthermore, structural problems started just three years later, with cracks appearing in ironwork due to ground movement on the southern side of the Severn.

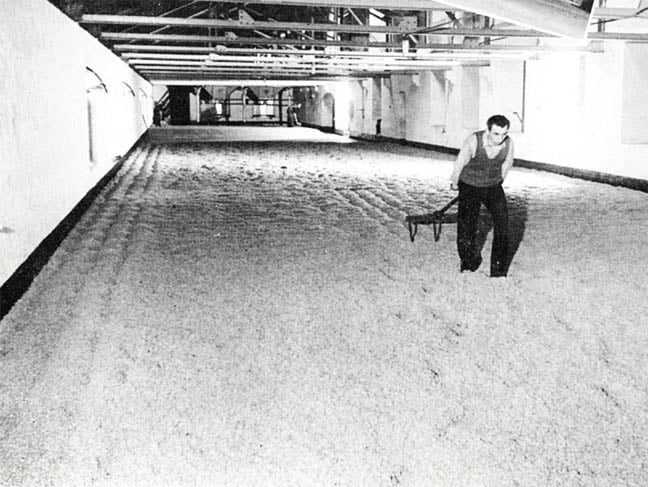

The mill's floors used for barley malting (Photo: Copyright Historic England)

But the bridge provided enduring proof that iron was a viable building material. You can still walk across it more than two centuries later, although its sides are currently covered in scaffolding and wrapping as part of a £3.6m conservation project. Its ironwork is being repainted dark red, thought to be the original colour.

Cut to 1796 and Shrewsbury businessmen Benjamin and Thomas Benyon partnered with John Marshall, a mill owner from northern England, to build a new flax mill in Ditherington on the outskirts of Shrewsbury. Fibre from flax plants was the wonder material of the age, used for everything from clothing and tablecloths to ropes and ship sails, and flax was grown locally and elsewhere in the British Isles.

But processing flax was dangerous as it generated flammable dust. Mills were built of stone or brick with timber frames and walls and staff worked long hours using tallow candles for light. Fires were common. Iron was designed to address that problem. "It was built as the world's first fireproof mill," says Alastair Godfrey, project lead for Flaxmill Maltings at Historic England.

The Benyons turned to fellow local Charles Bage, a man of many talents. He had worked as a wine merchant in Shrewsbury, an estate surveyor and the director of a local workhouse. Later he served as the town's mayor. But his interest in engineering connected him to brilliant local innovators, including William Hazeldine, an ironmaster whose work included the Llangollen Canal's Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, the highest in the world; legendary engineer Thomas Telford, who would collaborate with Hazeldine on projects including the Menai bridge that links Anglesey to mainland Wales; and Thomas Strutt, a builder of textile mills. In 1792, Strutt had come up with the idea of building mills with some iron columns, as well as encasing timber within brick and plaster, to make them less flammable.

At Ditherington and with Strutt's advice Bage went further, using iron for beams as well as columns and replacing almost all the wood with metal. "It was a quantum leap," says Godfrey.

There's a key difference between the Iron Bridge that predated Flaxmill Maltings: the bridge drew heavily on construction techniques used with wood, while Flaxmill Maltings was built in straight metal lines meeting at right angles. "This is thinking way outside the box, the first time anyone had thought in three dimensions," Godfrey tells me – even though the result was basically a big box.

Going up ... Third floor with different sets of columns (Photo: Copyright SA Mathieson)

On opening in 1797 the five-storey building, 177 feet long and 40 feet wide, had a working floor area of 31,000 square feet (2,880m2). Its iron frame was cast by Hazeldine, and it cost around £17,000, equivalent to about £1.8m today, with some funding from Charles Darwin's father.

Although it was not entirely fireproof, the iron-framed flax mill was much less flammable than its predecessors. The thin iron columns opened up internal space and, like the glass-faced metal buildings of today, allowed for much bigger windows and more light (this allowed staff to work longer with fewer candles). It was also one of the first steam-powered, mechanised mills in the world and was powered with coal brought in by a recently built canal, which is what allowed it be located near a centre of population to provide its workforce.

Bage would go on to carry out the first full-scale loading tests on iron roof frames, as well as building other iron-framed mills in Shrewsbury and Leeds. Innovation continued at the flax mill, which in 1805 became one of the first factories to install gaslights, several years before the streets of London – and allowing staff to work even longer hours.

At its height in the 1840s the flax mill employed 800 people. Locals called it the Dragon on the Hill because its serrated roof looked like scales. "It must have looked like an absolute alien," says Godfrey. "No building like this had ever been built in the world before, and it landed outside the county town of Shrewsbury using local people, local technology and local money to build it."

Leaving the visitor centre, we put on hard hats and hi-viz tabards to see some of the flaws that tend to arise with bleeding-edge technologies. The building's ground floor is a good place to see the original cross-shaped columns, which could cope with up to 2.5 times their normal load. If one was broken, those surrounding it could collapse under the extra weight.

"It's an absolute miracle the world's first iron-framed building still exists," says Godfrey. Supplementary hollow-tube columns were added in the 1880s; they now stand next to each other.

For all its positives, cast iron was also a problem. While it deals brilliantly with compression, it does less better with tension, where it tends to fracture rather than bend. The mill's brick walls settled downwards, while the lighter metal frame stayed where it was, leading to cracks in the cast-iron beams. As the 19th century progressed, new buildings switched to frames of wrought iron, which bends much more before it breaks, then to steel, as a result of improved manufacturing processes, which cut its cost.

In the 20th century, steel frames allowed city buildings to grow ever higher. Eventually, office and residential buildings replaced stone skins with metal and glass, while bridges and monuments took giant and fantastic shapes. Apart from a locally produced AGA, the final room in the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron consists of a montage of pictures: Paris's Eiffel tower, Manhattan's skyline, Sydney's harbour bridge and opera house, San Francisco's Golden Gate bridge, Gateshead's Angel of the North.

But as its descendants transformed the world's cities, Bage's big box was down on its luck. In the late 1800s cheap cotton largely replaced flax, and after lying derelict for a decade the mill was converted to barley malting, the industry in which Abraham Darby I had worked as an apprentice.

The new owners ripped out machinery, put in concrete floors and bricked up two-thirds of the windows. "That saved the building," says Godfrey – the blocked windows braced the increasingly fragile walls. On the evidence of the parts of the ground floor where the windows are still blocked, it must also have been pretty dark. According to Godfrey, the scaffolding is also helping to hold up the building.

We climb up inside the building. During the Second World War the building was used as a barracks known as the Rat Hotel by inmates; Godfrey shows off graffiti of wartime aircraft, uncovered by renovation. After the war it returned to work as a maltings, finally closing in 1987. Then it lay derelict while various regeneration plans came and went, its condition continuing to decline. Bage had not quite banished all timber from his revolutionary building, with oak ring-beams used to join the iron frame to the brick walls, and by the early 21st century decades of damp heavy malt had rotted the oak. The world's first iron-framed building was in danger of falling down.

First in class ... Iron Bridge demonstrated the viability of its name-sake material in civil construction (Photo: Copyright English Heritage)

In 2005 the site, which also includes the world's second and third oldest surviving iron-framed buildings, was acquired by English Heritage, a government body that among other things acts as a buyer of last resort for historic buildings. The work has since been transferred to Historic England. "We rescued it just in time," says Godfrey, who previously led work converting Plymouth's Royal William Yard to residential and commercial use. Last year, an ambitious regeneration project gained £20.7m from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The ground floor will become a museum, but the four floors above are going back to work as 28,000 square feet (2,601m2) of offices, providing employment for around 300 people. This is likely to include co-working space and an education provider, and the project is renovating other buildings on the site, with the nearby Dye House becoming a space for performances, pop-up restaurants and a micro-brewery.

We climb up to the third floor, where the renovation work, which started in June 2017 carried out by Croft Building and Conservation, has already opened many of the blocked windows. While it remains full of scaffolding the floor is flooded with natural light, and it's possible to imagine people at desks, taking a break from their screens to gaze at distant hills. Godfrey gives it the hard sell: when it opens in 2021, it will have a fibre-optic internet connection, an eight-minute walk to the railway station and easy access to Shrewsbury's great value housing. IT professionals are very welcome, he adds.

Shrewsbury Flax Maltings will be ready to work again (Photo: Copyright Historic England)

Shrewsbury today is a bustling town. A trip can wrap in a a number of other destinations including Shrewsbury Castle and Shropshire Regimental Museum with its commanding views, plus there's the site just north of the pivotal battle of 1403 that cemented the reign of Henry IV and laid the foundations for the Wars of the Roses. There's a riverboat tour and a Charles Darwin trail as well as shopping and refreshment options.

At its heart, however, iron is the core attraction. And while pioneering sites of the Ironbridge Gorge have been saved for history as museums, Flaxmill Maltings is going back to work. This seems appropriate: the world's first iron-framed building, like the nearby furnaces, factories and famous bridges, was built to make money. This big box helped create the modern world, but that was just a side effect. ®

GPS

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings Visitor Centre 52.72, -2.744

Postcode

SY1 2SX

Getting there

By Car: From the east, M54/A5 to Shrewsbury outskirts then A49 north, west on the B5062 and south-west on the A5191 towards Shrewsbury center.

Train: Shrewsbury station is 50-70 minutes from Birmingham New Street, with Flaxmill Maltings a short walk from the station.

Entry

Prices: Free for the visitors centre with tours organised by Friends of the Flaxmill Maltings.

Opening hours: April to October, 10am-4pm, Friday, Saturday and Sunday. November to March, 10am-4pm, Saturdays only.

Online resources

GPS

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron and the Old Furnace 52.639, -2.493

Postcode

TF8 7DQ

Getting there

By Car: From the east leave at junction four of the M54, from the west junction six and follow brown tourism signs for Ironbridge Gorge then Coalbrookdale Museums. A pay-and-display car park outside the museum costs £3 a day. Train: Telford Central train station from Birmingham New Street. Arriva bus 9 runs from Telford bus station (about half a mile's walk from the train station) to the Coalbrookdale Darby Road stop near museum entrance.

Entry

Prices: For Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron only, adults £9 (£9.95 with Gift Aid, seniors £8.10 (£8.95 Gift Aid) and children £5.90 (£6.50 Gift Aid). Annual passport tickets allow one visit to all 10 attractions run by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust in a calendar year, the latter being 5 per cent cheaper online, including the family-friendly Blists Hill Victorian Town and interactive Enginuity next to the iron museum. The Old Furnace is free.

Opening hours: Museum and furnace 10am-4pm seven days a week, 25 March - 30 September. 10am-4pm 1 October - 24 March but except Mondays.

Online resources

GPS

The Iron Bridge 52.6272, -2.4855

Postcode

TF8 7JP – tollhouse on the southern side

TF8 7AL – the Tontine Hotel on the bridge's northern side

Getting there

By Car: As above, then follow brown signs for Ironbridge Museums. The nearest car park, a few minutes' walk west along the Severn from the bridge, is at 52.6297, -2.4921.

Train: Train as above. From Telford bus station, take Arriva buses 9 and 18 and get off at Ironbridge the Square.

Entry

Prices: Free for both bridge and tollhouse.

Opening hours: Bridge and tollhouse 10am-4pm seven days a week, 25 March - 30 September. 10am-4pm 1 October - 24 March except Mondays.