This article is more than 1 year old

Ready for Glasto-net? Cheap, local low-power networks up for grabs in the UK

Ofcom proposes shakeup of spectrum bidding process

Some technologies lurking under the 5G umbrella promise to reshape the entire communications sector, creating new uses and businesses we can't imagine today. Ofcom showed it was hip to a few of these this week with a radical new way of opening up the airwaves.

Ofcom is allowing bidders to run their own local low-power networks at a very low cost, like selling electricity you generate at home back to the National Grid. And this won't even need 5G.

This was announced alongside Ofcom's 700MHz/3.4GHz spectrum auction on 18 December. It's a consultation on sharing three bands of spectrum with a new bidding model. So if you're a campus or an enterprise, a large public space around a town hall, theatre or stadium, you may be able to bid to run your own low-power local network, accessible using popular radio equipment such as a smartphone. Even temporary uses – "Glasto-net"* – are possible.

"It's a big deal, both as an immediate consultation and a reflection of a long-term trend which will see radio spectrum as a fluid resource," Bill Ray, Senior Director and analyst at Gartner, told us.

It's complementary to the MNOs, just as low-power community FM radio complements national professional broadcasters.

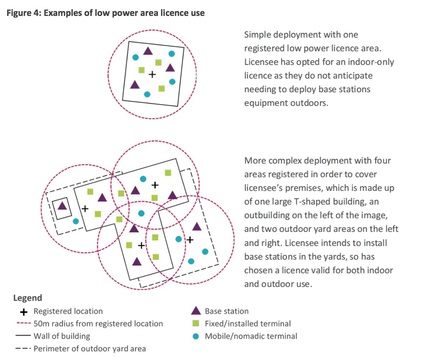

The proposal floats the idea of three new bands of spectrum for two uses: "low power" and "medium power". Ofcom said these licences will be "technically assigned based on BS location [that's "base station", not "bullshit"], power and indoor/outdoors" uses.

It will restrict outdoor height to 10m, and power to 24dBm per carrier (up to 3MHz) for low power, or 42dBm for the medium-power licences.

The spectrum is pretty tasty. The "1,800MHz" band referred to here is the old "DECT guard band", originally intended to protect digital cordless phones from interference. DECT evolved alongside GSM and the two were intended to work nicely together. This band was shared by 12 major licensees for low-power use, and Ofcom proposed freeing this up after those expired in 2016 (PDF).

It's complemented by shared chunks at 2,300MHz occupied by LTE, and 3.8GHz-4.2GHz, the latter having been identified as a key 5G band in Europe.

Ofcom suggested a potential bidder could grab all three for their location.

The big change, then, is in the pricing structure – a move away from auctions in which only big players who employ the best game theorists, economists and lawyers can take part. That model has made the Chancellor of the Exchequer pretty happy, but it clearly may not maximise the value of this spectrum.

How much is that temporary low-power network in the window?

All this requires a completely new approach to pricing, which Ofcom said is consistent with cost recovery. A 40MHz license could be £320, or 100MHz £800. This is priced for mass adoption. It could even encourage temporary uses for special events.

"The problem, for regulators like Ofcom and the FCC, is that their primary (stated) purpose is the efficient utilisation of radio spectrum," Ray said.

"The auction system was developed on the basis that the person who pays the most is the person who'll have most interest in using the radio spectrum, but this has been proved to be a fallacy. See Qualcomm's L-Band spectrum in the UK, or Indian spectrum dealings.

"The most efficiently used spectrum in the world is 2.4GHz, which is embarrassing for regulators who've been shouting that auctions are the best way to ensure efficiency (raising huge quantities of revenue being a happy side effect), so this is part of a big, and a very important, shift away from the auction system."

Ray also noted that incumbents have reasons for disliking it, as it devalues their existing spectrum holdings. And it's harsh on emerging economies who missed the windfalls of the 3G and 4G auctions.

The proposal isn't specifically focused on 5G, but 5G will help a lot. One of the MulteFire Alliance's goals is to get Wi-Fi, 4G and 5G to play nicely, but it goes beyond that – allowing enterprises and small venues to share spectrum.

How will your phone cope? Better with 5G than LTE, Ray suggested.

"If a network vanishes then the phone will just retune, as it does now if a signal disappears. With 5G a phone should be able to maintain connections to both a macro and micro network, so if the micro network (in shared spectrum) disappears then the user shouldn't notice."

There are some technical areas to work out. Not only is 2,300MHz used by some missile systems, it's also pretty close to the 2.4GHz unlicensed bands, where Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and hearing aids reside. But from LTE tests in this region at Victoria Station, Ofcom concluded "potential interference from 4G operating in 2,350-2,390 MHz was small and likely to affect only a very limited number of Wi-Fi users".

Further tests by the EU's JRC labs found noticeable interference only where the Wi-Fi base station signal was weak, the handset was on full power... and only a metre away. It also found that hearing aids weren't significantly affected as they recover the signal so well.

Ofcom hopes to publish a recommendation based on the consultation by Q2 next year, with licences up for grabs in the second half of the year. ®

* Like a wireless internet network for the world-famous music festival Glastonbury.