This article is more than 1 year old

Neptune-sized oddball baffles astroboffins: It has a good atmosphere despite star-lashing

First gas giant spotted in the so-called 'Neptunian Desert'

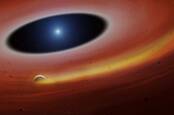

Astrophysicists have discovered a rogue exoplanet that has managed to cling onto its atmosphere despite lying fatally close to its parent star, defying all expectations.

NGTS-4b, nicknamed The Forbidden Planet, is a little smaller than Neptune, has twenty times the mass as Earth, and is located about 922 light years away. It’s locked tightly around a K-type main sequence star, and zips around it in just 1.34 days.

The close proximity means that the exoplanet is blasted with strong UV and x-ray radiation, bringing its surface temperature to a toasty 1,000 degrees Celsius – hotter than our system's Mercury. Under these harsh conditions, it’s unlikely to find any exoplanets of this size that can withstand a star’s constant lashing.

Scientists call this region close to the surface of a sun the Neptunian Desert. Here, most bodies disintegrate and lose their atmospheres, but not NGTS-4b. It’s the first of its kind to have ever been observed in this area.

“This planet must be tough - it is right in the zone where we expected Neptune-sized planets could not survive,” Richard West, first author of the research, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and a physics researcher at the UK's University of Warwick, said on Wednesday.

The hardy planet was discovered by the team using the Next-Generation Transit Survey, an array of 12 ground-based telescopes lying in the Atacama desert in Chile. The telescopes monitor the characteristic dip in a star’s brightness that signals an exoplanet is nearby: the planet blocks out the light from the star as it passes along its orbit. It’s a common technique known as the transit method to spot new planets.

“It is truly remarkable that we found a transiting planet via a star dimming by less than 0.2 per cent - this has never been done before by telescopes on the ground, and it was great to find after working on this project for a year,” said West.

The team aren’t completely sure why The Forbidden Planet has managed to keep its atmosphere. They believe the exoplanet may have migrated into the Neptunian Desert region as recently as a million years ago, so it may have escaped the star’s lashings for most of its life, or possibly its heavy rocky core may have played a part in retaining the atmosphere.

“We are now scouring out data to see if we can see any more planets in the Neptune Desert – perhaps the desert is greener than was once thought,” West concluded. ®