This article is more than 1 year old

DPL: Debian project has plenty of money but not enough developers

Project leader Jonathan Carter explains problems facing this key Linux distro

Debian Project Leader (DPL) Jonathan Carter has described the key problems in the Debian community as not a lack of funds, but rather a shortage of volunteer developers.

The project is tiny in comparison to the many thousands of organisations that depend on it. Ubuntu is based on Debian, as are other well-known distributions including Devuan, Kali, Knoppix, LMDE, Raspberry Pi OS (formerly called Raspbian), SteamOS and Tails.

There are other distros based on Ubuntu, not only the official variants like Kubuntu and MATE, but also those from third parties like Linux Mint, Linspire and Zorin. Debian itself is also widely used for running server applications, whether on-premises or in public cloud. It is also completely free. No surprise then to find Google and AWS among the platinum sponsors of the recent DebConf20 gathering. Debian is supported by a non-profit US organisation called SPI (Software in the Public Interest).

'Debianites don’t like spending money. They feel guilty'

In his "state of Debian" address at the virtual DebConf20, Carter outlined the finances of the Debian project, which are healthy. Across several Debian organisations including SPI, the project has over $900,000 in the bank, he said, and “if we ever do need money for something, [sponsors] will be there to help us.”

The culture of the community is not to spend money unnecessarily. “Debianites don’t like spending money,” he said. “They feel guilty.” We assume this has led to its reliance on a small army of volunteer developers who end up shouldering all the work.

Statistics on who is toiling away on Debian can be found here. Currently there are 975 uploading developers and 223 maintainers. That is not enough, according to Carter. Debian is getting bigger, he said.

In 2009, there were 22,000 binary packages for the i386 architecture in Lenny, the current release at the time. Today there are over 61,000 amd64 binary packages in Bullseye, the forthcoming release. After Bullseye, “100,000 packages is a serious reality on the horizon,” he said. The project needs to focus more on scaling accordingly.

Currently too many people take on too much responsibility...

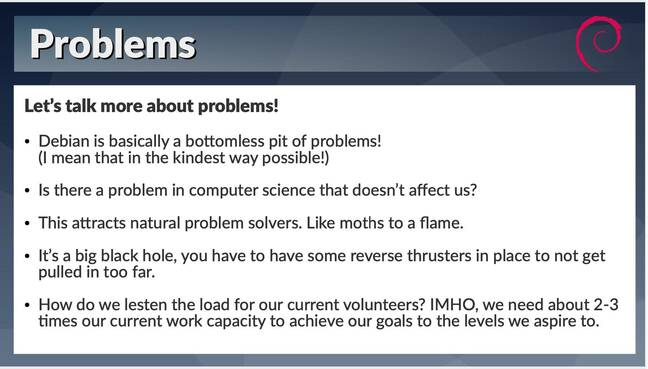

The biggest issue, though, is the people, not the processes. The work is demanding, he said. “Debian is a bottomless pit of problems. It’s inherent in the work we do. We’re affected by nearly every problem that exists in the realm of computer science.” This tends to attract volunteer developers who enjoy tough problems, and “it happens often that our lives are completely consumed by Debian,” he said.

“I’ve tried to calculate how much more volunteers we need to reach our goals to the levels we’d want and without increasing the stress on our current developers … at three times we could probably achieve all our goals. Currently too many people take on too much responsibility because they feel there is no one else who can do so.”

One possibility would be increased diversity. Carter is from South Africa and would particularly welcome more African developers, as well as more women, to work on the code. He also proposed increasing the number of local Debian events, such as mini conferences or user groups, which “lower the barrier of entry to the project.”

The way into Debian development should be made easier, he said, with better guides for onboarding, which may bring in more volunteer coders and maintainers.

The problem is not unique to Debian. Last month, Linux Foundation board member Sarah Novotny spoke to The Register about the challenge of lowering barriers to entry for new kernel developers.

Relying on plain-text email is a 'barrier to entry' for kernel development, says Linux Foundation board member

READ MOREAnother facet of the issue is that new packages can get stuck in the NEW queue awaiting approval. “It’s a sore point for many of us … many packages have got stuck there for a long time,” Carter said. This queue was at a record size earlier this year, though an effort from the team saw a big reduction in size in July.

The project is working to get itself better known, said Carter, but more can be done. They are talking to Lenovo about what it would take to get Debian on OEM laptops – though he remarked most Debian developers would immediately wipe and reinstall if they purchased such a thing. The biggest challenge, they learned, is having drivers for the latest hardware.

Typical Debian developers, said Carter, often use models that “aren’t available any more,” for example, old Thinkpads.

Despite Carter’s warnings about shortage of developers, it is also true that the capabilities and culture of the Debian project perform well and do a fantastic job both for the free software community, and for the many commercial organisations that depend on them.

“Debian developers are Debian users, too. The conflict between users and developers that often exists in the commercial world doesn’t exist on Debian,” explained Carter. Making it bigger and better known would only be a good thing if the culture that makes it work can be preserved.

The talk is available in the DebConf20 archive. ®