This article is more than 1 year old

Square Kilometre Array Observatory has a council now, so building super-sensitive €1.3bn telescope is next on agenda

But then there's the issue of mega-constellations to contend with

The long-awaited Square Kilometre Array Observatory (SKAO) has continued its march to reality with the launch of an intergovernmental organisation dedicated to radio astronomy.

The SKAO Council is composed of the observatory's member states and other countries wishing to sign up to the project. The first meeting last week was jammed full of policy and procedure approvals to turn the observatory into a "functioning entity."

The milestone follows the sign-off by countries such as the UK on the giant radio telescope after design work concluded.

Getting to this point has taken more than a decade of engineering design work and is a full 30 years since the concept of a next-generation radio telescope was floated.

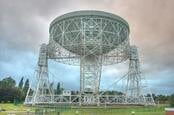

The challenge straddles nations. Almost 200 15-metre dishes are planned for the Karoo region in South Africa (64 already exist) and Australia will play host to 131,072 two-metre-tall antennas. The project is headquartered at the UK's Jodrell Bank site in Cheshire.

The name comes from the total collecting area – approximately one square kilometre – and scientists expect the radio telescope to be a good deal more sensitive than instruments currently in use.

It is an expensive endeavour. In 2020, the estimated cost for construction stood at €1.282bn and a further €0.704bn is needed for the first 10 years of operations to 2030. The construction phase is expected to last eight years, ending in 2028.

Things have also changed during the design phase, not least the determination of billionaires to spray the sky with satellites. A preliminary analysis of the affect on observations by mega constellations such as Elon Musk's Starlink was undertaken last year and confirmed that some tweaking was needed.

The study looked at the South African telescope and noted: "Without specific mitigation actions by the constellation operators, there is likely to be an impact on all astronomical observations in Band 5b."

That could result in a jump in observation times and was only based on a deployment of 6,400 satellites. 100,000 of the things raises the possibility of "threatening the viability of the complete Band 5b for 100 per cent of the time."

The issue is the frequency range used by the satellite industry, which is the same observed by Band 5b receivers. A relatively small number of visible satellites at fixed positions, thanks to geo-stationary orbits, can be handled. "The deployment of thousands of satellites in low earth orbit (LEO) will inevitably change the situation as astronomers now face a much larger number of fast-moving radio sources in the sky," the organisation said.

Still, the challenges of dealing with mega-constellations remain in the future. The first science opportunities from the telescope are not expected until the mid-2020s. In the meantime, the first meeting of the observatory's council is cause for some celebration.

And the future? Professor Philip Diamond, first director-general of SKAO, said: "The coming months will keep us very busy, with hopefully new countries formalising their accession to SKAO and the expected key decision of the SKAO Council giving us green light to start the construction of the telescopes." ®