This article is more than 1 year old

Battery recycling boosted by dentist-style ultrasonics, if manufacturers can cooperate

New technique quicker and greener, but needs batteries to be designed for dismantling

Boffins have laid claim to a "ground-breaking invention" which they say will make it considerably easier to recycle batteries from electric vehicles, laptops, and the like – an ultrasonic delaminator.

Electric vehicles may come with impressive green credentials, at least while they're being driven, but as any laptop owner knows batteries come with a finite lifespan. End-of-life EV batteries may find a second use as backing storage for power grids but there will come a time when they need to be recycled – and the current process is neither clean nor easy.

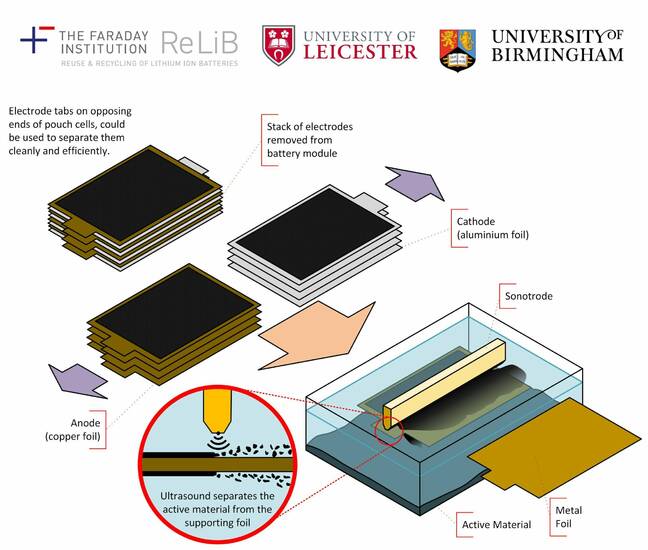

Enter ultrasonic delamination, a new technique for separating the materials in lithium-ion batteries for reuse, as discovered by researchers at the Faraday Institution, the University of Leicester, Swansea University, and the University of Birmingham.

"This novel procedure is 100 times quicker and greener than conventional battery recycling techniques and leads to a higher purity of recovered materials," claimed Andy Abbott, professor at the University of Leicester. "It essentially works in the same way as a dentist's ultrasonic descaler, breaking down adhesive bonds between the coating layer and the substrate.

"It is likely that the initial use of this technology will feed recycled materials straight back into the battery production line. This is a real step change moment in battery recycling," he added.

"For the full value of battery technologies to be captured for the UK, we must focus on the entire life cycle – from the mining of critical materials to battery manufacture to recycling – to create a circular economy that is both sustainable for the planet and profitable for industry," commented Pam Thomas, PhD, chief executive of the Faraday Institution, which runs the Reuse and Recycling of Lithium Ion Batteries (ReLiB) programme.

- Inventor of the graphite anode – key Li-ion battery tech – says he can now charge an electric car in 10 minutes

- Tesla owners win legal fight after software update crippled older Model S batteries

- Hyundai and Singapore's top telco charge towards electric vehicle battery subscription service, 5G smart factories

- OVH writes off another data centre – SBG1 – and reveals new smoking battery incident

"This effort to deliver commercial, societal and environment impact for the UK is showing great promise. It is imperative that academia, industry and government redouble their efforts to develop the technological, economic and legal infrastructure that would allow a UK EV battery recycling industry to become established to realise the full benefits of a decarbonised transport sector."

The current state of the art in lithium-ion battery recycling relies on shredding batteries then immersing the remains in concentrated acids in order to remove graphite and lithium, nickel, manganese, and cobalt oxides from the electrodes. The ultrasonic system, by contrast, can operate as a continuous-feed process using extremely dilute acids or plain water - and results in the recovery of greater quantities of purer materials.

The trick, as is always the case with such research, will be getting the technology out of the lab and into industry. Here, the team has a head start: its invention is an adaption of a system currently in use in the food preparation industry. Discussions are under way with "several battery manufacturers and recycling companies," the Faraday Institution has confirmed, with a view to installing a demonstration system at an industrial site by the end of the year.

It'll take industry cooperation to commercialise the system, sadly: the Faraday Institution notes that in order for the batteries to be disassembled ready for processing, they must first be designed for disassembly. At present, many battery manufacturers glue components together to boost stability – which makes them difficult, or even impossible, to separate for end-of-life materials recovery.

The team's work has been published under open-access terms in the journal Green Chemistry, while a patent has been applied for ahead of its hopeful commercialisation. ®