This article is more than 1 year old

Western Approaches Museum: WRENs, wargames, and victory in the Atlantic

Anonymous Liverpudlian building was once home to the strategists who beat Germany's U-boats

Geek's Guide To Britain Walking down the ramp into the Western Approaches Museum in Liverpool you are faced with a quote from American journalist David Fairbanks White, author of Bitter Ocean: The Battle of the Atlantic, 1939-1945. It states boldly that Derby House is where the Second World War was won. That's quite a claim for a rather bland 11-storey office block in the Stripped Classicism style that most people have never heard of.

With the fall of France and the rescue of some 330,000 British and French troops from the area around Dunkirk in the early summer of 1940, it became obvious that, assuming Britain survived the immediate crisis and decided to fight on, the war against Germany would be long and dependant on the movement of goods across the Atlantic from the then neutral USA.

The vital task of coordinating Royal Navy activity in the Atlantic and the management and protection of the merchant convoys – one of the few lessons that the Royal Navy had remembered from the First World War – was the responsibility of the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, based in Plymouth, a location soon determined to be less than ideal due to its potential vulnerability to German bombers and warships based in France. Liverpool, the destination for the majority of the transatlantic convoys, was the obvious choice for a new location and so it was that on 7 February 1941, the new Western Approaches headquarters was established beneath Derby House, under the command of Admiral Sir Percy Noble.

The ladder that WREN's scaled to update the plot board are as dangerous as they look. LACW Patricia Lane fell to her death off one on 25 April 1943

Luckily for Britain, Germany's navy, the Kriegsmarine, was nowhere near ready. Before the outbreak of war, U-boat commander Admiral Karl Dönitz had predicted that a fleet of 300 would be needed to sink enough ships to cripple Britain's ability to fight. In 1939 he had just 26 ocean-going boats at his command. It was only in August 1942 that the German U-boat fleet broke the 100-barrier.

The Operations Room has been recreated as faithfully as possible to look as it did in the second half of World War 2

Despite this weakness in the German submarine arm, Dönitz's plan to group his U-boats into so-called wolfpacks boded ill for the Allies. In October 1940 six U-boats closed in on Convoy SC7 which was protected by 11 escorts, including two destroyers and three corvettes, and sank 22 ships. This represented the highest loss of any convoy during the entire war, a rate that was simply unsustainable. Clearly the Royal Navy needed to develop new tactics to overcome the U-boat threat and secure the transatlantic supply routes.

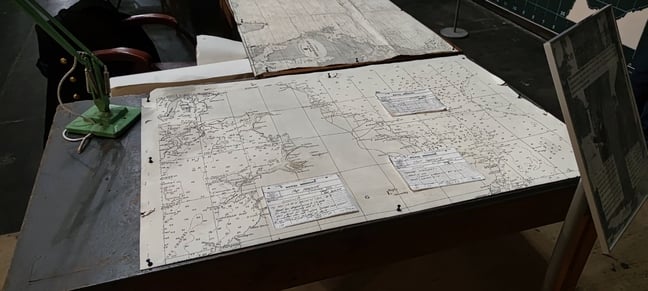

The main plot board at Western Approaches Command. Recreated here is the progress of Convoy ONs 5, the engagement which is often regarded as a turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic

The grim proceedings in the Atlantic were being carefully monitored in Liverpool. Designed to be both bomb and gas-proof, the bunker below Derby House, colloquially known as both the Citadel and the Fortress, had a seven-foot thick roof (2.1m), three-foot (90cm) thick walls, and originally consisted of scores of rooms (rumoured to number 100 or more) covering some 30,000 square feet (2,787m2). Only a small part of that area is open to the public and as recently as 2017, the company that now runs the site, Big Heritage, was still finding sealed-off and hidden rooms in the complex, unopened since the final days of the war.

The battle for the Atlantic was painstakingly recreated in real-time on the vast plot walls in the command room. Here staff would scale vertiginous wheeled ladders to place wooden markers representing the position of Allied merchantmen and warships and, at best guess, German U-boats. The availability of other assets such as Fleet Air Arm aircraft was also noted, turning the walls into a comprehensive representation of the life-and-death struggle at sea.

Halfway up the wall opposite the main plot board, the commanding officer could survey the drama through a window that made up most of one wall of his office.

The office of the commanding officer of Western Approaches HQ. Here he could watch the Battle of the Atlantic unfold on the giant plot boards in the next room

While the Battle of the Atlantic was being monitored and coordinated in the Western Approaches Operations Room, the work of a unit called WATU was being conducted on a linoleum covered floor 11 storeys above. While the activities in the bunker below Derby House have become relatively well known, what was done on the top floor is a rather less familiar story.

Captain Frederick John 'Johnnie' Walker was the Royal Navy's more successful U-boat hunter but his tactical plan Buttercup was flawed, as WATU proved

The upper floor of Derby House was home to the Western Approaches Tactical Unit under the command of Captain Gilbert Roberts, who had designed wargames while serving at the Royal Navy's Tactical School in Portsmouth before the war, and his predominantly female staff from the Women's Royal Naval Service or WRENs.

The task given to Roberts and his team when it was established on 1 January 1942 was simple – develop tactics for the Royal Navy that would defeat the U-boats and win the Battle of the Atlantic. Wargaming was Robert's chosen medium, re-enacting Atlantic engagements and trying out new tactics in what looked like a vast and complex version of the popular board game Battleship.

The wireless telegraph room carried orders from the Commander, Western Approaches to the Royal Navy as it fought the Battle of the Atlantic

The tactic most widely taught at WATU was a nocturnal manoeuvre called Raspberry (and its derivatives, the Half-Raspberry and the daylight version, Gooseberry), so-called because it was hoped it would blow a raspberry at Hitler. This tactic was built upon the realisation by Roberts and his WATU staff that U-boats were striking from within the convoy formation then diving and waiting for the convoy to pass overhead.

Raspberry called for the escort group to fall back behind the convoy group and pounce on the U-boat when its commander thought the danger posed by any escort vessels had passed and surfaced. It was an immediate success.

The role of WATU wasn't just to decide what did work, but also what didn't. The Royal Navy's foremost U-boat hunter, Captain Frederick John Walker, scored one of the navy's first major successes of the war against the U-boats while escorting convoy HG.76. Though an escort carrier and two merchantmen were sunk, Walker's escort group sank two German submarines.

Walker was convinced he had a system that he christened Buttercup. It fell to Roberts and his team to game test Buttercup and conclude that its success – based upon the escort group turning away from the convoy and hunting down the first U-boat spotted with all available ships – was due more to luck and Walker's aggressive spirit than sound, repeatable tactics. Walker was right about one thing, though – the ships in the escort group needed to work as a team.

The canvas booths used during WATU's war games were designed to give Royal Navy crew the same limited view of the battle area that they would have from the bridges of their escort ships

Another significant contribution of WATU was providing evidence that the creation of Support Groups – dedicated units of escort ships that would loiter in the mid-Atlantic waiting to be called upon to reinforce the escorts of beleaguered conveys – was a good idea.

Admiral Noble had proposed the idea but it had been rejected due to a lack of suitably fast warships to form the groups. His successor from November 1942, Admiral Max Horton, had a brainwave – reduce the size of the convoy escorts to free ships for the Support Groups. Again the Admiralty turned the idea down.

The cavernous Command Room is the hub of Western Approaches HQ and is still pretty awe-inspiring today. Note the window in the commanding officer's station at top right

In a final bid to change minds one of Robert's aides at WATU, Captain Neville Lake ran a game based on the progress of two real convoys – HX.229 and SC.112. This battle, described by German radio as "the greatest convoy battle of all time" resulted in the loss of 21 allied ships. Lake's game, which included the actions of an imaginary support group, predicted that eight of those ships would have survived.

The report based on Lake's wargame was the prime factor in convincing Winston Churchill to give Western Approaches HQ the extra ships. Horton had asked for 15 destroyers but by the end of 1943, he had 20, divided into five groups of four, ready to dash to the aid of any threatened convoy. From this point on in the war, the Royal Navy's anti-submarine activities were as much offensive as defensive.

ONs 5 was a convoy the Germans were determined to destroy with one of the biggest U-boat wolfpacks of the war. The Royal Navy was equally determined to protect it and sink U-boats. The RN prevailed

The crunch came in May 1943 when the Germans assembled one of the largest wolfpacks of the war to destroy the convoy ONs (Outbound, North America, slow) 5. Over the course of a week, more than 40 U-boats attacked the convoy, sinking 13 out of 42 ships, but with the loss of seven U-boats and seven more badly damaged. In total 41 U-boats were sunk that month and May 1943 came to be known as Black May to the German U-boat force.

- Talking a Blue Streak: The ambitious, quiet waste of the Spadeadam Rocket Establishment

- Fancy that! Craft which float over everything on a cushion of air

- Come on kids, let's go play in the abandoned nuclear power station

- TAT-1: Call the cable guy, all I see is a beautiful beach

- Come kneel with us at UK's Cathedral, er, Oil Rig of the Canal: Engineering masterpiece Anderton Boat Lift

In the face of such losses, Dönitz started to withdraw his submarines from the North Atlantic. The raw numbers bear witness to the Allied success. In 1942 U-boats sank 5.8 million tons of shipping. In 1943 that figure dropped to 2.3 million tons and in 1944 to 600,000 tons.

The green chalk lines representing the U-boats were impossible to see by the ships' crews in their canvas booths, imitating the invisibility of their real undersea foes. Thus were operational manoeuvres like Raspberry taught to RN crews

By the time WATU closed in 1945 more than 5,000 naval officers had played the wargames run by Roberts and his WRENs (66 in all) and attended more than 130 different courses covering all aspects of anti-submarine warfare. And it wasn't just the Royal Navy that benefited. Crews from the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, Denmark, and Belgium to name but a few were trained in WATU's tactics.

The final room of the museum gives a taste of what the WATU game floor would have looked like with its canvas booths and the plots of convoys, U-boats and escorts chalked out on the floor in different colours. The booths were designed to restrict the view of naval crews who came to train at WATU in such a way as to mimic the limited view they would have from the command decks of their warships.

On the floor, the chalk tracks of the U-boats were drawn in green, to make them invisible to the escort commanders in their booths.

The white chalk lines that denoted the position and course of the escorting warships and their merchantmen wards could be seen from the booths. In this way, WATU hoped to match the situation on the high seas as closely as possible.

Of course, WATU and Western Approaches HQ didn't defeat the U-boats by themselves. Improved technology like ASDIC (an early form of sonar) and the Type 271 radar, the high-frequency direction finding, HF/DF or "huff-duff" system, the breaking of the German Enigma cypher by the codebreakers at Bletchley Park, Hedgehog, a forward-firing mortar system that allowed Royal Navy ships to attack U-boats running ahead of them, and the USA's massive Liberty ship merchantman building programme which launched over 2,700 ships between 1941 and 1945 all played a part.

But it was at Derby House that this massive programme was coordinated in action and at WATU that the tactics for its best use were devised.

The self-guided tour of Western Approaches HQ takes between one hour and 90 minutes depending on how long you linger. There are quite a few interesting things to look at including the hotline to No. 10 Downing Street and the various cypher machines that linked the bunker to the outside world including Bletchley Park.

The prime attraction is the Operations Room with its huge plot boards and the WATU room with its canvas booths, used by naval crews to play their wargames and learn the tactics devised by Roberts and his team. The Operations Room has remained exactly as it was left when the doors were closed on 15 August 1945, though the plot boards have been set to show the situation immediately before the climactic battle of ONs 5.

The top-floor rooms that housed WATU were converted back to civilian use at the end of the war but a temporary exhibit dedicated to the unit's work was set up at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich in 1948. That the work at WATU faded from public knowledge was largely due to the 50-year restriction placed on the junior staff speaking about their work.

Sea Captains and Admirals received special dispensation to discuss WATU in their memoirs – though few did – but the WRENs who played such an important part in the operation were told to keep quiet. That the command bunker survived was due to the walls and roof being so massive that altering the space was wholly impracticable.

The bunker was mothballed in 1945 and fell into disrepair until it was first reopened as a museum in 1993.

Western Approaches Museum

1-3 Rumford Street, Exchange Flags, Liverpool, L2 8SZ

https://liverpoolwarmuseum.co.uk/

53.40759, -2.99327

Admission prices

Adult – £13.50

Concession (under-21, over-65, ex/serving forces, emergency services) – £11.50

Children (5-16) – £8.00 (additional children will be £4)

Children under 5 – Free

Served in WW11 – Free

Getting there

The museum is a 15-minute walk from Liverpool Lime Street railway station and there are two NCP car parks a stone's throw away. Being slap bang in the middle of Liverpool there is plenty more to see and do in the vicinity and an abundance of places to eat and drink.

Further reading

A Game of Birds and Wolves by Simon Parkin ISBN 978-1-529-35321-1

The Battle of the Atlantic by Jonathan Dimbleby ISBN 978-0-241-97210-6 ®