This article is more than 1 year old

Amazon Game Studios to its own devs: All your codebase doesn't belong to us

E-goliath's subsidiary drops 'draconian' contract terms that absorbed personal work, demanded license rights

Analysis Amazon Game Studios has reportedly dropped terms in its employment contract that gave the internet giant a license to the intellectual property created by employees, even to games they develop on their own time.

The expansive contractual terms received some attention last month when James Liu, a software engineer at Google, recounted via Twitter how in 2018 he turned down a job offer at Amazon "due to absolutely draconian rules regarding hobbyist game dev."

His Twitter post from July 6, 2021, since deleted, included a screenshot of a contractual agreement that laid out specific terms by which employees were allowed to develop or release "Personal Games."

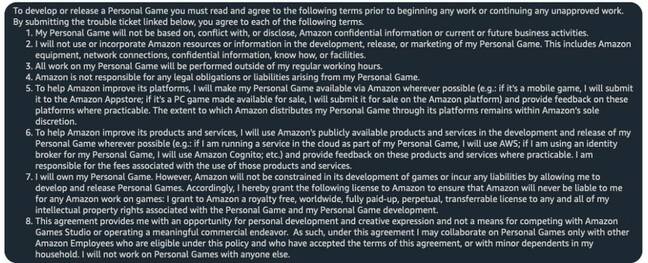

The contract included requirements found in many employment contracts that any personal projects not conflict with obligations to Amazon and that work on such projects occurs outside of normal work hours. But it also made some unusual demands.

The agreement required that employees make their personal game available through Amazon where applicable – an Android game would have to be submitted to the Amazon Appstore – and use AWS services on the backend, if the project relies on cloud services.

It also required that employees collaborate only with other Amazon employees who have accepted the terms of the agreement or with minor dependents in the employee's household.

And it required the employee to grant Amazon "a royalty free, worldwide, fully paid-up, perpetual, transferable license to any and all of [the employee's] intellectual property rights associated with the Personal Game and the [employee's] Personal Game development."

Amazon did not respond to a request to confirm a Bloomberg report that Mike Frazzini, head of Amazon Game Studios, announced the elimination of the controversial rules in an internal email to staff.

Amazon's not alone in this

Other companies have made similarly broad claims on the intellectual output of their workers. Google, at least until last month, included a link on the documentation page of the Google Open Source website outlining its Invention Assignment Review Committee (IARC).

The now deleted page began, "As part of your employment agreement, Google most likely owns intellectual property (IP) you create while at the company. Because Google’s business interests are so wide and varied, this likely applies to any personal project you have. That includes new development on personal projects you created prior to employment at Google."

The page explains why the IARC was created: "We understand and sympathize with the desire to explore and ship technology projects outside of Google" and went on to outline how employees should submit a project for IARC review to get Google to renounce ownership.

Google did not immediately respond to a request to explain when it removed its IARC page and whether that reflects a change in policy.

- Amazon staffers took bribes, manipulated marketplace, leaked data including search algorithms – DoJ claims

- Flying camera drones, cuddly Echo gadgets... it's all a smoke screen for Amazon to lead you gently down the Sidewalk – and you'll probably like it

- Amazon continues its tsunami of announcements, now with AI in mind. We spoke to an AWS lead to decode it all

- Petition instructs Jeff Bezos to buy, eat world's most famous painting

Sharon Vinick, a partner at employment law firm Levy Vinick Burrell Hyams LLP in Oakland, told The Register that while Amazon Game Studios is based in Washington State, its agreement likely wouldn't work in California, where the state's Labor Code section 96(k) empowers the California Labor Commissioner to investigate wages denied as a result of lawful conduct outside of work.

Vinick said while she hasn't been involved in a case where a dispute of this sort has been litigated, the issue does come up, usually in the context of an employee moving from one company to another who then makes some work available to the new employer.

Those disputes, however, she said, while they may involve cease-and-desist letters and chest thumping tend not to amount to much unless the work at issue proves to be exceptionally valuable.

Asked whether the increase in people working from home has created more disputes of this sort, Vinick said she expects that's true though it's too early to tell because such claims haven't worked their way through the legal system.

"I do think you're going to start to see a lot more of these as remote working expands," she said.

There may also be a mitigating factor: In July, US President Joe Biden issued an executive order that asked the Federal Trade Commission "to curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility."

If FTC does so, perhaps in conjunction with future legislation, Vinick said that may moderate some of the more restrictive contractual requirements, particularly those in southern states, that limit worker mobility. ®