This article is more than 1 year old

How legacy IPv6 addresses can spoil your network privacy

One bit of kit using EUI-64 screws up protections – study

A single device within an IPv6 home network can reduce the privacy of every computer, handheld, and other gadget on that network, enabling all devices to be tracked around the internet, even those with IPv6 privacy protections.

In a research paper titled "One Bad Apple Can Spoil Your IPv6 Privacy," Said Jawad Saidi, of the Max-Planck-Institut für Informatik at Saarland University in Germany; Oliver Gasser, also of the MPI-INF; and Georgios Smaragdakis, of TU Delft in the Netherlands describe how the use of legacy IPv6 addressing standard EUI-64, aka Extended Unique Identifier, by just one device potentially degrades privacy to every device on that network.

Their paper is scheduled to be published next month in ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, Volume 52, Issue 2.

IPv6 was introduced in 1998 as the successor to IPv4, the internet addressing protocol that emerged from DARPA in 1981. IPv6 is still being rolled out – about 38 percent of those connecting to Google.com currently do so over IPv6 connections. But IPv6 is necessary to allow new devices to be added to the internet as IPv4 addresses become scarce.

Depending on your ISP, router, and so on, you might find that on your home network, your laptops, phones, and other devices have their own local IPv6 addresses, and each have a public-facing IPv6 address when connecting to websites and other stuff online. These addresses should be regularly swapped out with new ones so that when you visit a website today, and visit it again tomorrow, it's not clear to the website from your IPv6 address alone that your device has returned, granting you some level of privacy. According to this research, if you have a device on your network with EUI-64, you lose this.

IPv6, the paper explains, relies either on DHCPv6 or stateless address auto-configuration (SLAAC) to assign client addresses. With SLAAC, a router will send a prefix – in a way, the network identifier in an address – to the client, and the client will then select an IPv6 address within that prefix – known as the host part the address, or interface identifier (IID).

The IID used to be based on an encoding of the device's hardware MAC address, known as EUI-64 [PDF]. It subsequently became clear that EUI-64 should be considered harmful to privacy because it exposes hardware identifiers at the network layer.

Back in 2007, IPv6 privacy extensions were proposed to randomize the host portion of the address. And ISPs got into the habit of rotating IPv6 address prefixes as an additional privacy defense.

Sadly, some hardware makers – largely Internet-of-Things vendors – missed the memo and still use EUI-64 to generate a device's IID.

- Microsoft Azure DevOps revives TLS 1.0/1.1 with rollback

- Nominet suspends 'single digit' number of Russian dot-UK domain registrars

- Network operating system Dent 2.0 targets smaller firms

- IPv6 is built to be better, but that's not the route to success

What the paper's authors have found is that it just takes a single device using EUI-64 to deny privacy to every device on the network. Almost a fifth (19 percent) of all end-user prefixes at a large ISP were found to be affected by this privacy leak and, it's claimed, a slightly smaller percentage (17 percent) can be monitored by large internet companies and hyperscalers.

"By analyzing passive data from a large ISP, we find that around 19 percent of end-users’ privacy can be at risk," the authors state in their paper. "When we investigate the root causes, we notice that a single device at home that encodes its MAC address into the IPv6 address can be utilized as a tracking identifier for the entire end-user prefix — even if other devices use IPv6 privacy extensions."

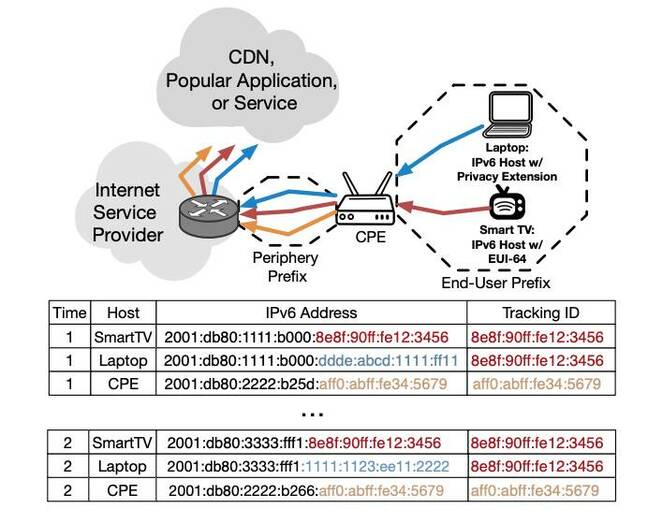

The paper describes an example involving two devices, a laptop using IPv6 privacy extensions, and a smart TV using EUI-64, both using a home network gateway router with IPv6 connectivity upstream and SLAAC in use. The diagram below, taken from the paper, is given to illustrate this scenario.

The TV and the laptop are, on day one, given the same end-user prefix (2001:db80:1111:b000) and then their own host portions to form a public-facing IPv6 address. By the next day, another prefix is generated (2001:db80:3333:fff1) though the EUI-64-based TV gets the same host portion while the laptop gets a fresh one. The laptop has an entirely new IPv6 address whereas the TV only has a new prefix.

If the TV and laptop on day one interact with CDNs and internet giants, and then interact with those providers again on day two, one or more of those large networks can work back from the TV's unchanged host portion (8e8f:90ff:fe12:3456) and new prefix to link the laptop's latest IPv6 address with its previous address. Thus, the laptop can be tracked, with the TV's host portion effectively becoming a tracking ID.

This only works if the TV and the laptop both access the same cloud or CDN providers – such as Google, Meta, or Netflix, or something like a DNS or NTP provider – and if those backends care enough to match up people's IPv6 addresses and then use that information for something. It's perhaps unlikely though the mechanism is there. In the above diagram, CPE refers to the customer premise equipment aka the broadband gateway box. If this doesn't have the same end-user prefix as the devices on the network, it can't be tracked via this method.

"Since the smart TV is not using privacy extensions, it allows CDNs and other large players in the internet to track not only the smart TV itself, but all devices within that end user prefix," the paper added.

The MAC address can also be extracted from the EUI-64 portion of the IPv6 address and used to determine the device maker, via the Organization Unique Identifier (OUI) part of the MAC address. Devices not using EUI-64 could not be identified this way, even though they could be tracked using the common IID.

The boffins said about 39 percent of the network prefixes hosting EUI-64 devices correspond to companies making only IoT devices. About 32 percent correspond to companies making various devices, including IoT, computers, and mobile hardware.

In this second category, the paper's authors observe, while Apple enables privacy extensions by default in their products, other vendors do not.

"Unfortunately, at the time of writing, many Linux distributions do not activate privacy extensions by default," the paper says. "Products using Linux derivatives in their software are likely unknowingly putting their users’ privacy at risk."

The authors speculate that this may be due to the fact that the original privacy extensions specification recommended deactivating them by default, which is no longer the case in the current standard.

They also urge regulators to require that vendors certify their products for IPv6 privacy compliance and ISPs to check their gateway routers for privacy issues before shipping them to customers. ®