This article is more than 1 year old

How did ESA's gamma ray-spotting 'scope make it to 20? They totally overdid it

We speak to the boffins behind the mission about hits, misses, engineering, and that extraordinary near death scrape

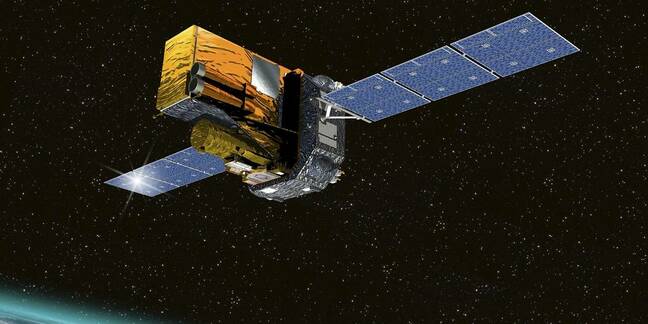

This week, the European Space Agency's International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory (Integral) spacecraft celebrated the 20th anniversary of its launch – although it was only meant to last five years.

The satellite left Earth's atmosphere on the back of a Proton rocket from Kazakhstan on October 17, 2002, after first being proposed in 1989 and selected for development in 1993.

It was slated to provide imaging and spectroscopy of electromagnetic radiation in the 15 keV to 10 MeV energy range, meaning it would observe the likes of black holes, nova and supernova explosions, neutron stars, and more for what was initially five years. But the thing about Integral is it kept going and going and going in its highly eccentric orbit.

At least once I think we rotated the wrong way, but with the help of a couple of Excel spreadsheets, and three teams working the problem, we got there

Set sail for a five-year tour

"Nobody considered it would live more than five years," Integral's former mission manager, Peter Kretschmar told The Register. "When we reached 10 years, we thought it was super. I honestly remember talking to Richard [Southworth], our spacecraft operations manager nowadays, and we looked at each other and said wouldn't it be so great if it could actually manage 20 years?"

Those who played a part in its history met at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, this week to reminisce and honor the spacecraft's third decade in operation. Some attendees spent the bulk of their career working on the mission, like Kretschmar and Southworth.

Kretschmar has been steadily involved with Integral since he received a postdoctoral position with the mission while it was still in development in 1996. His wife has even worked on the project developing hardware. To Peter, Integral is not only his career, it's a family affair – and in his own words has "shaped [his] whole life."

Kretschmar likened his role to that of a captain or navigator. "They aren't calling me first before they make sure the satellite is safe, but they call me later if there's a real problem."

Southworth compared himself to a taxi driver, even though he's the highest technical authority on the mission nowadays and has been with the program for 24 years. "Scientists tell me where to go and when," he said.

One person who wasn't surprised by Integral's longevity was mission scientist Erik Kuulkers. "There is a certain knowledge that X-ray missions or gamma ray missions last longer than expected," he told The Reg. He explained that because there is a lot of radiation affecting the instruments in space, they get over-engineered and therefore last longer than people would think.

Integral's bus design is similar to XMM-Newton, ESA's X-ray space observatory that launched in 1999. The design choice helped cut costs on the project. However, Integral is around 500lbs (227kg) heavier, with very different instruments. Its four scientific instruments are the heaviest ever put in orbit by ESA, coming in at approximately two metric tons.

According to ESA, this is due to the need to shield the large detectors from background radiation while they capture sparse and penetrating gamma rays.

Integral, if it were designed today

Southworth said if the mission were designed today, a few things would be different. For one, it would feature highly automated operations with little contact time, rather than intensive manual operations.

This is because when it was developed, reliable onboard recording telemetry was not available. With no mass memory storage devices, everything was in real time, meaning constant connection to the ground station was required 24 hours a day.

Additionally, there was no reliable way of storing an onboard telecommand queue, eliminating any notion of automated operations.

"It's quite likely that instead of being in an elliptical Earth orbit, we would be at the L2 Lagrange point, which is further away from the Sun than the Earth," said Southworth. "One of the disadvantages to being in Earth orbit is that we pass through the Van Allen belts every perigee, which gives us very high background radiation and we have to put the instruments in a safe configuration."

Southworth said the orbit led to the loss of six to eight hours of observation time per 64-hour revolution, a situation that would be completely unnecessary with today's technology.

Kuulkers added that although the main difference if Integral was designed now would be communication with the craft. The instruments on a modern version would also have been devised to optimize current science and research.

"But just imagine what kind of ancient equipment we have onboard and it's working perfectly. It's amazing," said Kuulkers.

Kretschmar was quick to warn that any improvements wouldn't change costs as the main expenditure comes from launching the thing into orbit.

"As soon as you put anything into space, it is easily a few 100 million just for that, depending on the size of your satellite, and the cheap ones only get up there because they can hitch a ride on something bigger," said Kretschmar. He conceded that private space may soon be a game-changer in this arena.

- Darmstadt, we have a problem – ESA reveals its INTEGRAL space telescope was three hours from likely death

- NASA OKs spacewalks, upgrades helmets after fishbowl mishap

- Moon has been drifting away from Earth for 2.4 billion years, rocks reveal

- NASA's Lucy probe dodges space traffic around Earth in gravity-assist flyby

Should we stay or should we go now?

The spacecraft is slated for re-entry via a planned long-term orbital drift in February 2029, but it could meet its demise earlier if it doesn't get funding. This means it could unceremoniously end up space junk, despite 20 years of passion and funding behind the project.

After the first five years, the program was on rolling extensions of two or three years, based on a technical review.

"Money is even shorter now than it has been at any time in the last 20 years so there is more doubt about the next mission extension," said Southworth. Kuulkers attributed the scarcity of funding to the situation in Ukraine, inflation, and the destabilizing effects of COVID-19.

Regardless, Southworth said he's beginning to think it might last its full 27 years until 2029, although he admits by then the performance might be rather poor because "the instruments are starting to degrade and so are the solar arrays."

Integral currently operates without thrusters, using its reaction wheels and solar radiation pressure in its stead, thanks to a failure in July 2020 when the spacecraft unexpectedly went into safe mode.

"Science continues, technology continues," said Kuulkers. "Industry wants to move on, they want to devise new instruments and new satellites. For them, it's just another kind of job."

But without a successor for at least the next four or five years, the world could miss some big opportunities to observe and learn.

For instance, on October 9, Integral recorded the brightest gamma ray burst ever recorded. The event, named GRB221009A, is thought to be caused by the explosion and collapse of a star about 30 times bigger than the Sun, resulting in a new black hole about 2.4 billion light-years away.

"The universe doesn't stop. And every now and then new things pop up, and you want to be there. I mean, it's already up there – so why turn it off?" said Kuulkers. "That would be a shame."

In pre-pandemic mid-2018, the combined scientific papers being published about Integral or XMM-Newton had hit the rate [PDF] of one every 29 hours since launch. At the time, it brought the total to around 5,600 papers.

"You have some data which you don't get from other satellites," Kretschmar told The Reg. He said that because of how Integral records data, it can observe incidents that are too bright for other observatories.

Second chance at life

In some sense, Integral has already had a second chance after recovering from a near-death experience in September 2021. One of the three active flywheels that helps stabilize attitude turned off without warning, causing it to rotate dangerously. Without its thrusters working from the July 2020 event, and just three hours of battery life remaining, the team almost lost Integral forever.

They were miraculously able to reactivate the wheel and stop the spacecraft from wobbling, all while working from home, and learning through trial and error how to recover the spacecraft on the fly.

"At least once I think we rotated the wrong way, but with the help of a couple of Excel spreadsheets, and three teams working the problem, we got there," Southworth told The Reg. He said the team didn't really celebrate, it was 5am, so they all went back to bed and cleared up the mess in the morning.

Southworth conceded that the team's most creative moments overall were born of the after-work beer garden.

And that's the thing: many of those involved with Integral really do care about the project.

"When a satellite like that gets in trouble, you literally have retired engineers working with some of the companies who built the satellite who were contacted by somebody who still works on it," said Kretschmar. "They sit down and spend possibly days thinking about any ideas they might have, and I don't think anybody ever gets paid for that input. People will work far beyond any contractual requirements to make it work." ®