This article is more than 1 year old

Orion reaches the Moon, buzzes surface, gets ready to orbit

We're back - for the first of many missions to come

NASA's Orion spacecraft has arrived at the Moon, and even swung around the dark side, as it prepares to settle into an orbit around Earth's biggest satellite that will take it further from home than any (eventually) manned spacecraft before it.

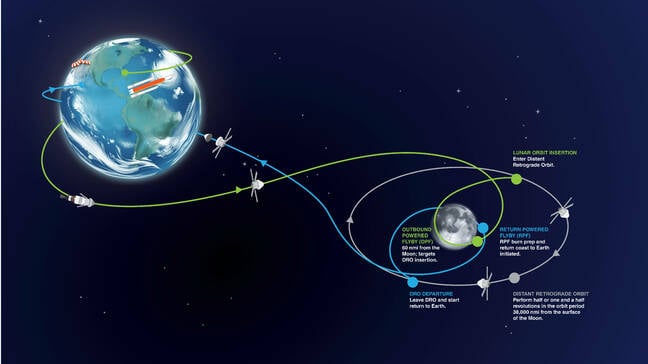

Orion used its orbital maneuvering engine for two and a half minutes to accelerate around the moon for a gravitational assist NASA called the "outbound powered flyby burn," the first of two maneuvers the capsule will need to make to get into a distant retrograde orbit, or DRO.

This Friday, November 25, Orion will perform the second maneuver, an insertion burn, which will put it into its DRO to test the capsule's ability to function in deep space.

Distant retrograde orbits are known to be incredibly stable for reasons similar to the functioning of Lagrange points that hold the James Webb Space Telescope in a reliable spot: A gravitational equilibrium between two big celestial bodies. In this case, it's the Earth and Moon.

DROs are retrograde in relation to the direction the Moon travels around Earth, and are distant in the sense that Orion will end up flying more than 57,250 miles beyond the Moon at its furthest point in the orbit - further than any space capsule before it.

A map of Artemis I's flight path showing the DRO (in grey)

On Monday, November 28, Orion will be at its furthest point from Earth - more than 268,500 miles into deep space, while the spacecraft will reach its farthest point from the Moon this Friday.

While out in the cold recess of DRO space performing science experiments for between 6 and 19 days, Orion will also be giving NASA a chance to test its systems for the Artemis II mission, which will see the manned craft fly out to the Moon and back in May 2024 (for now).

"Without crew aboard the first mission, DRO allows Orion to spend more time in deep space for a rigorous mission to ensure spacecraft systems, like guidance, navigation, communication, power, thermal control and others are ready to keep astronauts safe on future crewed mission," said Artemis Mission manager Mike Sarafin.

Mixed news for Japan’s Artemis payloads

While Orion is doing fine, one of the ten CubeSat payloads that launched on the same rocket – Japan’s “OMOTENASHI” moon lander – won’t complete its mission.OMOTENASHI – the Outstanding MOon exploration TEchnologies demonstrated by NAno Semi-Hard Impactor mission – is a 6U cubesat that includes a small (0.715 kg) surface probe intended to crash into the Moon.

The probe has an inflatable airbag and shock absorption system comprising crushable material and an epoxy filling, designed to allow survival in surface impacts at target speeds of 50 m/s vertical and 100 m/s horizontal. Those speeds occur after a few hundred meters of free fall under lunar gravity, so OMOTENASHI offered the chance to test another way of delivering payloads to Luna.

Sadly, however, the CubeSat’s radios proved unresponsive not long after launch, and the orbit chosen for OMOTENASHI gave it just one chance to engage its thrusters and head for the Moon’s surface.

Japan’s space agency today reported it could not establish contact with OMOTENASHI and was therefore unable to send the commands to initiate the landing sequence. OMOTENASHI has therefore failed.

Another Japanese CubeSat on the Artemis mission, the EQUilibriUm Lunar-Earth point 6U Spacecraft (EQUULEUS) is performing as expected on its mission to measure plasma in the Earth/Moon system, during which it orbit both the Moon and Earth.

- Simon Sharwood

Return to sender

Orion will perform a departure burn to get itself out of DRO, which will take it to within 60 miles of the lunar surface and put it on a course for home. The craft still has one more burn to make though, and it's where things start to get interesting.

The final burn will combine with a gravity-assist from the Moon that will "slingshot Orion on a trajectory back home where the Earth will accelerate [it] to a speed of about 25,000 mph (40,233 kph)," NASA said.

For reference, Orion was cruising at 5,102 mph (8,210 kph) after performing the two-minute burn that took it around the dark side of the Moon.

Traveling at 25,000 mph has a side effect that NASA is relying on for one additional Orion systems test: It'll heat the capsule to around 5,000°F (2,760°C) - half the temperature of the Sun's surface - during atmospheric reentry.

But first thing's first: Let's get that spacecraft into its lunar orbit and celebrate our return to the Moon (albeit remote for now), after 50 years of gazing up and wondering "what if?"

Speaking after Orion emerged from the dark side of the Moon and images of Earth were beamed back, flight director Zeb Scoville had a chance to articulate what many have been thinking as Orion zipped through the void. "This is one of those days that you've been thinking about and talking about for a long, long time." ®