Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/03/20/feature_the_story_of_the_camputers_lynx/

The Lynx effect: The story of Camputers' mighty micro

The cat from Cambridge that clawed its way to the top... almost

Posted in Personal Tech, 20th March 2013 12:19 GMT

Archaeologic Not all of the early 1980s British home computers were fated to be as successful as Sinclair’s ZX series or Acorn's BBC Micro. Many were destined instead to be loved solely by keen but small communities of owners. For all these users’ enthusiasm, there were too few of them to sustain the cost of developing, manufacturing, marketing and evolving the products they had selected. When the crunch came - and after 1983’s poor Christmas sales season, it came with a vengeance - the makers of these machines were doomed.

Even superior technology was no guarantee of survival as the minds behind the Lynx, made by Cambridge-based Camputers, were to find out.

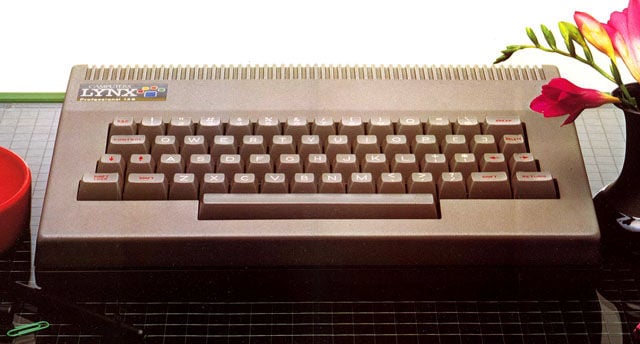

Camputers' Lynx: a cat without nine lives

The Lynx’s own origins go back to early 1981 when Richard Greenwood, founder of small Cambridge-based electronics design company GW Design Services (GWDS), decided to establish a second firm to make and sell microcomputers. It was called Camtronic Circuits, though it was later renamed Camputers.

Greenwood’s career stretched back to the late 1960s and an apprenticeship with Pye Electronics. In June 1977, he set up on his own firm, establishing GW Draughting Services to do sub-contracted circuit boards. “Dick was mainly doing PCB layouts,” recalls Geoff Sore, who had trained as an apprentice alongside Greenwood. “In those days this was done with red and blue tape onto clear plastic film usually at 2:1 size ratio, sometimes life-size, and that was a very laborious and very skilled job, because you not only had to manipulate the tape, you had to work out all the tracking.”

By October 1979, Greenwood found himself increasingly taking on electronics design work, so the "Draughting" was dropped from the company name and replaced by "Design". Camputers was formally incorporated in February 1981. Geoff Sore says the name was conjured up not only because Greenwood wanted something more catchy than GWDS, but in order to put clear blue water between the group’s efforts for clients and the work it would do for itself.

“I used to live with Dick in a shared flat when we were apprentices at Pye,” he remembers. “People came, did their apprenticeships and left, so the turnover in the flat was quite high. He went his way, I went mine. I was working in Malmesbury, Wiltshire as Euro Sales Manager for one of the Philips companies, and I got totally pissed off with it all. I gave it up and started doing sub-contracted design work. I met Dick again, and he said, ‘Why don’t you come and work with me?’ So I did.” Sore joined GWDS in January 1981 just before the foundation of Camputers.

Camputers' first Z80 micro

GWDS’ business grew and around this time was contracted to design a Z80A-based CP/M computer for a London-based firm called Iona. According to Sore, GWDS built Iona a number of prototypes, but the client seemed to lose interest and eventually the project just fizzled out, but it got Greenwood thinking about how GWDS might itself branch out into computers.

It was around this time that John Shirreff, who had trained as an architect but discovered he had a flair for electronics during his experimentation with electronic music, joined the team as a circuit and systems designer. “He was the real design genius, he had the flair for coming up with novel approaches to things,” Sore recalls. Martin Crutchley, who had been with GWDS for some time, was in charge of mechanical engineering.

“At that time we were developing peripherals for the BBC Micro under contract,” Sore remembers. “We did the floppy drive. Dick did the BBC Micro PCB layout. He would work the whole day doing modifications, and then at night I would drive from Cambridge to Norwich to take the new masters to the PCB plant out there. They would make the boards the next day and deliver them back down to Acorn, and they’d build it and play about with it, and a new set of mods would come across to us.”

GWDS also did some contractual work on early versions of the NewBrain during 1981.

All these efforts only reinforced Richard Greenwood’s belief that the GWDS team had what it took to make their own machine. “We had all the facilities, but we didn’t have the money to get more staff, to fill the gaps,” says Sore. “Dick gave me shares in GWDS, and he went off to look for funding, while I ran GWDS.”

With the BBC Micro finally put into production at the end of 1981 and its debut on sale in early 1982 - though still no real sign of the NewBrain, mind - Greenwood decided to go ahead. And, in March 1982, he established a team to create what would become the Lynx. John Shirreff got to work designing the system architecture, while Greenwood himself worked on the look of the case, Martin Crutchley handling its tooling and mechanics.

Software star

At this point, GWDS’ other business was going sufficiently well to hire a young, 23-year-old maths graduate called Davis Jansons to write the new machine’s software. He wrote most of the code on Tandy TRS-80 and Nascom hardware until a prototype Lynx became available. His wife, Sue, agreed to write the new machine’s manual.

The “adrenaline soaked” development effort - bear in mind, many of the GWDS team were also working on designs for the company’s clients - ran through the summer of 1982, with the first prototype booting up in July. That gave Greenwood the confidence to seek out funding to continue development, and was able to persuade Barclays to loan the company £50,000, later increased to £75,000.

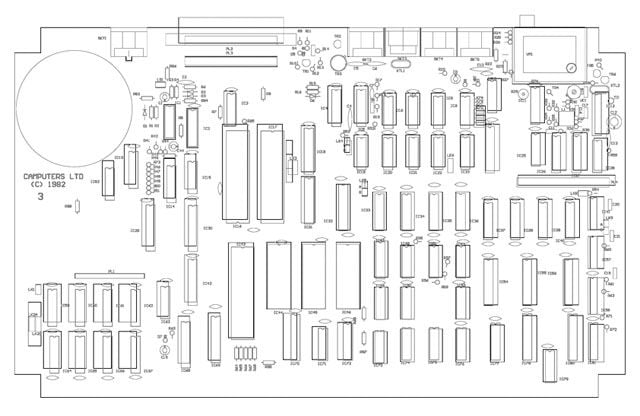

The Lynx's motherboard layout

Today, John Shirreff recalls Lynx development effort being a relatively straightforward one, much of the groundwork for features like switching between banks of memory having been already done during the Iona work. Unlike the GWDS’ previous machine, however, the Lynx required new work to be undertaken on colour graphics, TV output and sound.

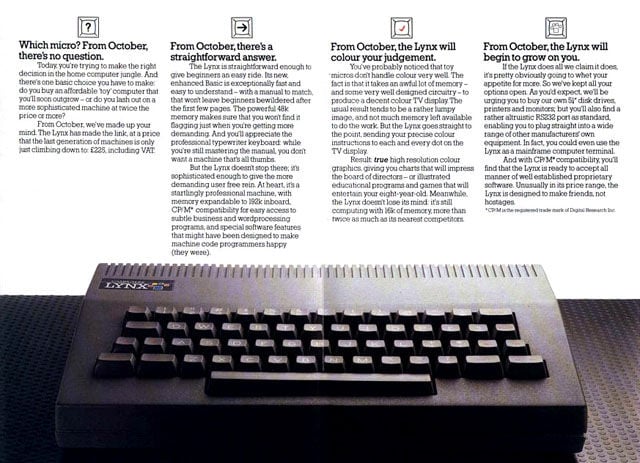

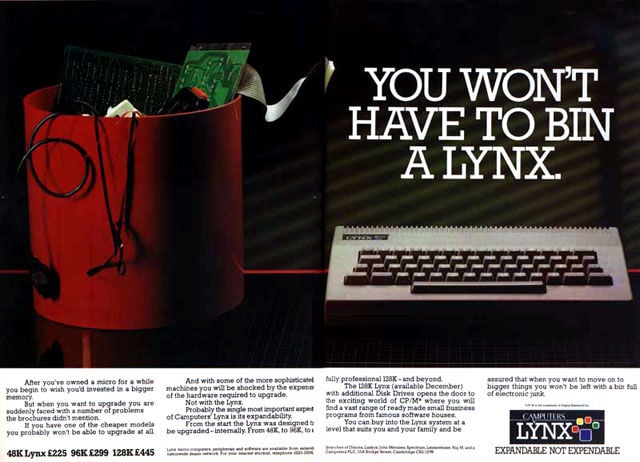

The development work went sufficiently well for the company to book a stand at the following September’s Personal Computer World Show to demonstrate a prototype and to brief the press about the machine, though and initial price point for the 48KB Lynx, of £150 including VAT, was revised upward to £225 just before the show. Camputers was able to announce that it would offer 96KB and 128KB models in addition to the 48KB version, and that these would be able to run the CP/M operating system on their Z80A processor - an obvious choice for the computer’s CPU given the work GWDS had already done on the Iona micro.

Good crit

During September 1982, Camputers moved from Cambridge’s Hill Street to the more central Bridge Street opposite The Mitre and Barron of Beef pubs - the latter site of the famous physical confrontation between Sir Clive Sinclair and Acorn’s Chris Curry, though the fight wouldn’t break out for a few years yet.

Jansons’ powerful Basic would be placed along with the hardware drivers - written by Shane Voss and Fiona Miller - and such into 16KB of Rom. The Rom’s graphics routines were written by Michael Behrend and Ron Penrose. Of the 48KB Ram on board the basic model, 32KB was assigned to the Lynx’s bit-mapped 256 x 248 hi-res display, which could be extended to 512 x 248 with extra Ram. Each pixel was “accessible and colour programmable”, said Shirreff, who had designed the device to be readily expandable.

In September 1983, Camputers was expecting to ship the Lynx the following month

“The whole design philosophy was linked to expandability - particularly now that memory is becoming so cheap,” he told Popular Computing Weekly early in September 1982. “The main difficulty with the design was its memory banking arrangement. I think we have developed a convenient and unconventional system which has many speed and software advantages.

“The machine has been designed to switch memory in 64KB blocks - larger units than most micros. There are problems switching 64KB units on the Z80A - you end up switching the section you are executing. But there are new ways round these problems. Because of its memory banking, the Lynx can run CP/M. Most low-cost micros will not run CP/M because the Rom gets in the way.

“This sets the Lynx apart from other micros making it more flexible. You can keep hanging on extra 64KB blocks of memory indefinitely.

“If the Lynx is used as a graphics terminal for a mainframe - for which it is well suited - you can dump a screen full of information into the work space, manipulate it, and put it back. The Z80 is a very good processor with a long future, particularly for bit manipulation. The snag is that it doesn’t have a fixed access time, but the Lynx gets round this.”

Fully working prototype

Shirreff was confident that the remaining bugs could be sorted out and the machine could go on sale in October. The prototype put on show was, says Geoff Sore, “a working unit. It wasn’t a keyboard on an empty box with everything underneath. There might have been a few link wires in it, of course” but it wasn’t ready for release. The Basic needed further debugging, and there were still some timing issues to be ironed out on the main board; the manual wasn’t ready, either.

Indeed, come October and Camputers had to admit that it had delayed the release of the machine to mid-November. Even that proved a little optimistic - production didn’t begin until December, and then only in small quantities, Sore recalls. “We did actually ship some in December 1982, not many, but some. Real production didn’t really get going until after Christmas.” Not bad, perhaps, for a machine that hadn’t even existed on paper nine months earlier.

Some machines went out to computer magazines for review, others to software companies who had expressed an interest in developing applications for the Lynx. Not that Camputers felt confident in the ability of those firms to get programs out quickly. A dearth of software prompted the foundation of CamSoft to fill the gap. Meanwhile, retail deals had been struck with the Spectrum chain and Laskys, who together took almost all of the machines being punched out in the new year: 900 were assembled in February, with the monthly output rising to 1000 by May. Lynxes started to appear in shops in March 1983, by which time Camputers had shipped 2000 units, it said later.

The reaction of early users and reviews was generally positive. “The Lynx is simply a good micro. It has no wonderful outstanding qualities, but in every department of its specification it ranks alongside the best. It is as though the designers took the best features of all the popular micros and put them together in one box,” wrote Bill Bennett in the February 1983 issue of Your Computer. “So the Lynx represents a consolidation of previous advances as well as a tiny advance of its own. By utilising technology that has already passed the test of time, it should have fewer teething troubles than some micros which aim to break new ground.”

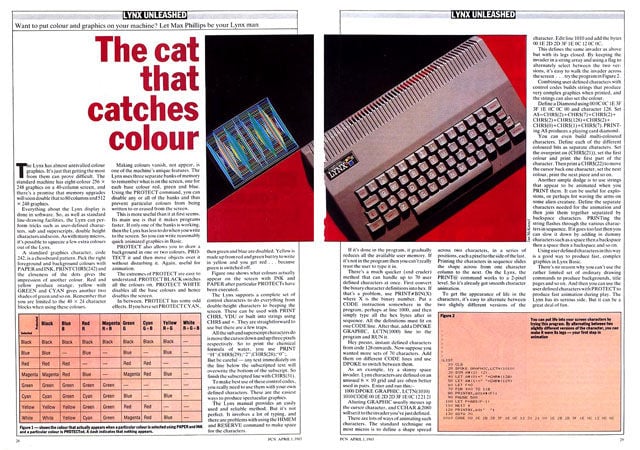

Superb graphics

Yet there were aspects of the Lynx that allowed it to stand out from the crowd. “The graphics on the Lynx are perhaps its strongest feature. Resolution is high, and unlike most other home computers all eight colours can be mixed on the same screen,” noted Bennett. “There are 256 x 248 pixels, and a good set of commands to use them to create some very good graphics.”

Computing Today’s Don Thomasson, in the magazine’s June 1983 issue, noted that: “The display uses 32-column hardware to generate a 40-column screen format, by the simple expedient of using a 6 by 10 character matrix instead of the more usual 8 by 8 pattern. This allows the 40 columns to be covered by 240 bits, where other systems use 256 bits for 32 columns. The concept is simple, but its consequences are not, especially as three complete screen RAMs are used, one for each primary colour.”

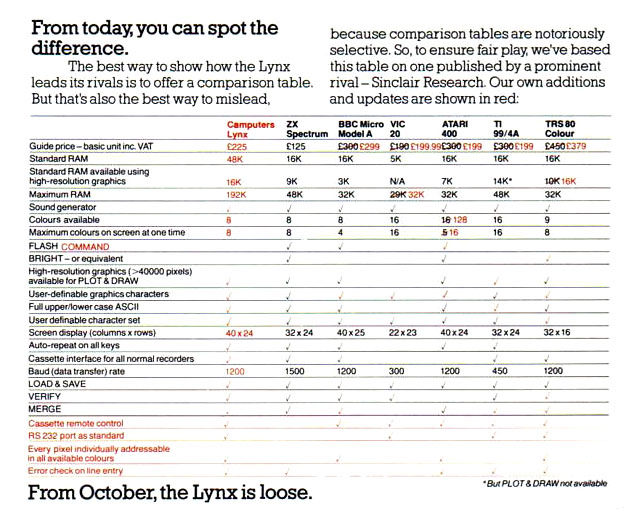

How Camputers saw the Lynx lining up against the competition

Max Philips, writing in Personal Computer News, praised the Lynx’s “almost unrivalled colour graphics... Everything about the Lynx display is done in software. So, as well as standard line-drawing facilities, the Lynx can perform tricks such as user-defined characters, sub and superscripts, double-height characters and so on.

“The Lynx uses three separate banks of memory to remember what is on the screen: one for each base colour red, green and blue. Using the PROTECT command, you can disable and or all of the banks and thus prevent particular colours from being written or erased from the screen.

This is more useful than it at first seems. Its main use is that it makes programs faster. If only one of the banks is working, then the Lynx has less to do when you write to the screen. So you can write reasonably quick animated graphics in basic.”

Basic quirks

Your Computer's Bill Bennett also lauded the Lynx Basic’s support for inline machine code instructions. “What will attract people is a simple-to-use machine-code facility. The monitor in the Lynx’s ROM allows the user to write and edit programs written in machine code. [The] CODE [command] allows you to store machine code in a Basic line. LCTN is in effect a pointer to the first byte of machine code stored in a CODE line: it is used as an ordinary variable. Type CALL to tell the computer to execute the machine-code sub-routine held in one of the CODE lines, which is specified by LCTN. Bytes of data can pass into and from the Lynx via the I/O port at the rear. This can be done using the commands INP and OUT.”

Tim Langdell, writing in Popular Computing Weekly, gave a thumbs up to Davis Jansons’ Basic. “What [Jansons] has managed to cram into the 16KB of Rom is quite incredible. He has created a new Basic with similarities to Microsoft, BBC and Sinclair Basic... The Lynx Basic is structured as the BBC machine’s is - with Procedures, If-Then-Else, and so on - but goes further than the BBC by having While and Wend too.”

Personal Computer News praised the Lynx's graphics - as did other magazines

Not that the Basic was perfect. Thomasson, as other reviewers did, pointed to the Lynx’s weak sound support in Basic: “There is a BEEP command specifying 'wavelength', number of cycles, and loudness, the last varying from quiet to inaudible.”

Maggie Burton, reviewing the Lynx for Personal Computer World, noted Jansons’ Basic “includes some very odd qualities indeed... First and foremost, it won't allow multi-statement lines. Now, quite a few older machines are the same, and Jansons explained he did this to improve readability of listings. But the alternative in the area of code-cramming is to use line numbers with a decimal point! This means you can have a huge number of lines in a program - four figures after the point are allowed - and this is far more than you could ever need... One of the [other] major disadvantages of the Lynx is the fact that it will only accept single-letter variable names, although the interpreter distinguishes between upper and lower case.”

And the aforementioned praised-by-all smart graphics came at a cost: “One of the worst penalties is that the screen does not scroll, wrapping around vertically instead, but this is usually relevant only to listings and dumps. The use of the main processor, plus a specialised display chip, means that action is necessarily slower,” judged Thomasson. That was one reason why the Lynx attracted so few action games to its roster of software.

Basic quirks

“Lynx seems to have struck a very good middle ground in trying to please the serious user, the first time buyer of a home computer, and the small business user. In many ways, the Lynx must rival micros costing at least twice as much (such as the BBC Model B and new SuperBrain) in the business sector, as well as offering extremely strong competition to micros in the £175 to £225 region such as the Dragon 32, the Vic and the 48K Spectrum,” concluded Langdell.

Meanwhile, as had been the case in 1982, Camputers was finding money a problem. In March 1983, the company arranged a £300,000 loan from Barclays. That, and the confidence in customer demand expressed by their retail partners, persuaded the Camputers bosses to plan a major rights issue. It would offer 6.4 million shares in the newly constituted Camputers Plc, now effective owner of GWDS and CamSoft. The goal: to make £900,000 with which to pay back that £300,000, up Lynx production, develop more software and to complete the development work on the other Lynxes in the line-up.

These had still failed to appear. The problem was the disk drives, says Geoff Sore. These had been farmed out because of Camputers had no experience writing firmware or a disk operating system - and it lacked the financial resources to hire in suitable talent. The £299 96KB machine was intended to go out with extra Rom - 4KB of it - to support the drives and add extra Basic commands. Camputers didn’t want to release the 96KB machine without the drives because as soon as the machine came out, the company would have to offer an upgrade path to 48KB owners: extra slot-in Ram and Rom chips. It didn’t want them to then have to upgrade a second time when the drives finally appeared.

“The 48K wasn’t premature, because on its own it did everything we wanted it to do,” recalls Geoff Sore. “For full forward compatibility you have to develop the last model first and then strip it back down to the basic machine, but we didn’t really have the time or the money to do that. We’d have gone bankrupt before we shipped. We knew the 48K couldn’t use the disk drive because there was not enough memory, but the Spectrum and such were out, and there was huge pressure to get revenue.

“The 96K was basically just a memory addition and some added features in the Basic. But that coincided with the disk drive; we wanted to make sure the 96K would work with the disk drive, and as I say there were problems with the disk operating system, and it cause a lot of heartache. I suspect the 96K could have been shipped a lot earlier, but we would have had to take them back to swap the Rom to support the drive.”

Drive delays

The drives were due early 1983, but were then promised for April and, when that deadline came up, for June. “The RS232 port is not entirely functional at present and the hardware boys are wrestling with it as a top priority,” Personal Computer News was told. Camputers demo’d the 96KB Lynx at the Earls Court Computer Fair in June 1983, after which it emerged the machine wouldn’t now be out until September - a year after the Lynx had its first public outing.

The drive delay also hindered work on the 128KB Lynx, on which Camputers’ attack on the business market would be based since it was the only machine of the three to have enough free Ram to run CP/M. Shipping the 128KB Lynx, and the 96KB model too, was among the key predicates for Camputers’ June 1983 forecast of £750,000 pre-tax profits by 31 March 1984, highlighted in the company’s rights issues prospectus.

Come September 1983, the 96KB Lynx did indeed go on sale complete with the augmented Basic Rom. Owners of 48KB machines were able to upgrade for £89.95, a process that involved returning their computers to Camputers, which would swap out the Rom chip and add the extra 64KB by way of a daughter-card into one of the slots John Shirreff had designed in specifically for it. The release of the 128KB Lynx was now scheduled for later in the autumn. It was formally re-announced in December, when Camputers bosses must have understood that it could ship the following year. It did, but not until March 1984.

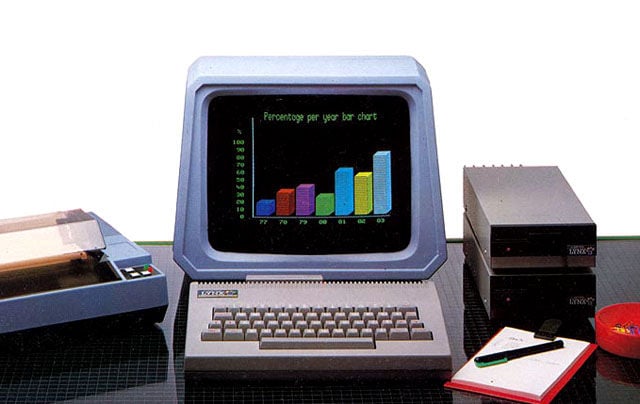

Camputers promoted the Lynx's expandability

The 128KB Lynx comprised a new motherboard, updated Basic, a high resolution 80 column x 24 row text screen, and CP/M 2.2 using the standard disk drives. The 48KB and 96KB Lynxes both used a Z80A microprocessor clocked at 4MHz, but the new top-end model incorporated a 6MHz Z80B microprocessor, giving a substantial speed improvement. Unfortunately, contrary to what Camputers had previously stated, the souped up Lynx was not fully compatible with software written for the earlier models.

“At some point we decided the Z80A wasn’t fast enough to run CP/M,” remembers Geoff Sore. “The 128 was a effectively a Mark 2 Lynx - there were quiet a lot of differences in the hardware structure, and that unfortunately affected some of the software, so some of the 96K software wouldn’t run on the 128K, contrary to the marketing.”

Business in trouble

There was a lot riding on the 128KB model. Christmas 1983 had not yielded the sales volumes Camputers and many of its rival manufacturers were anticipating. “We shipped a lot of units into retail through mid-1983, but at Christmas they just weren’t selling,” says Sore. “I don’t know what was selling, but it wasn’t computers.”

The 128KB was pitched at businesses and professional users, though you have to wonder now how many of these potential buyers would pop into Laskys or Dixons for their office equipment. Certainly, retail remained the focus of Camputers’ sales efforts, but the troubled Christmas and scary prospects of a very weak home computer market through 1984 prompted the company to emphasise the 128KB and its role in business.

In 1984, Camputers' future was riding on the 128KB Lynx and its hoped-for business audience

Enter, then, a rebranding exercise: the 48KB Lynx became the Leisure, the 96KB model the Laureate, though the name would be later appended to the 128KB Lynx too. The 48KB model was dropped by Camputers’ retail partners, who would to focus solely on the 96KB and - eventually - the 128KB models; the Leisure became a device only available through mail order. Its price was cut to £160. The Laureate was bundled with a pair of disk drives, a parallel interface and a copy of Perfect Software’s suite of productivity apps, all for just under £700.

But many observers questioned Camputers’ health. Dick Greenwood was encouraged to step down as Chairman, to be replaced by Stanley Charles of the company’s stockbroker, Statham Duff Stoop, which had organised the share issue the previous year. Charles pitched the rebranding as an attempt to change Camputers’ image, but he confirmed that the company was seeking further funding - a sign it was not selling enough computers.

“We have now reached agreement with a financial consortium,” Charles announced in March 1984, “and we are just waiting for the stock exchange paperwork to go through before we make a formal announcement about it.”

No one to the rescue

But their potential angel got cold wings and pulled out. Come May, Charles was forced to admit: “While one party has expressed an intent to ensure that the Lynx series will continue, no firm offer has been made.” The writing was on the wall. 24 members of staff were laid off - among them John Shirreff, he told me - and a creditors meeting called for early June. Charles’ hope that a would-be buyer would snap up the company before that meeting were dashed, and there was little choice left but to go into voluntary liquidation.

Camputers’ debts totalled £1.8 million, with £877,000 of that owed to its parent company, Plc. The firm’s total assets were estimated at £94,250.

Through the summer joint liquidators Hacker Young & Partners and Cork Gully negotiated two possible takeover deals, one with paper and stationery company Spicers, but neither came to anything. “There is still some interest being shown but there is not very much time left. Within a month someone will have to be found to continue with the project or it will have to be broken up and the parts sold off,” a spokesman for Hacker Young told Personal Computer News in October.

Two months later, Camputers finally closed down and its assets were sold to Anston Technology, a Cambridge firm founded specifically to buy Camputers’ assets, for which it paid £24,000, it was claimed at the time. One of Anston’s directors also ran Braefield Chapman, one of Camputers’ assembly sub-contractors and which would have undoubtedly been one of the firms owed money by Camputers. It had Lynx stock and pre-assembly components on hand. Dick Greenwood was asked to advise Anston on where it might take the Lynx range. “My purpose is to ensure that the Lynx continues,” he told PCN. “I’m currently tying up loose ends from a technical and production point of view.” He would soon become, with Chapman, joint head of Anston.

In February 1985, Anston announced that it would begin selling the 128KB Lynx, promising to cut the price from £399 to £299 and offer a 1MB disk drive for £269. The 48KB and 96KB models were culled. But there’s no sign the revived machine ever came back to the market, certainly not with any significant presence. By now Oric had also collapsed; Acorn, having teetered on the brink, had been saved by Olivetti; and Sinclair, a year after the launch of the business-oriented QL, was having a tough time - it would later be forced to consider taking money from publishing tycoon Robert Maxwell. Only Amstrad appeared to be flourishing.

Thirty years on

Looking back, Geoff Sore says: “We had to differentiate ourselves from the Spectrum because of the price differential. We were trying to appeal to a better class of customer, a more technical customer, but it was a much more capable machine, but it wasn’t as good at fancy, flashy games. And indeed the Commodore 64 eclipsed the Spectrum and everything else because of its games capability. We failed to fully appreciate the power of the games market, and we never really got to grips with getting enough output on the games side. That’s one reason why we didn’t sell enough machines.”

It is estimated that around 30,000 Lynxes were sold in total, only a third of them in the UK - the rest were bought in Europe. That’s rather less than the 40,000 units Camputers told journalists as the start of 1983 that it expected to produce that year alone.

Geoff Sore left Camputers in August 1983. After stints at Control Universal, a maker of Eurocard-format BBC industrial controllers, and at Pye, he founded a business manufacturing custom keyboards for industrial applications and, in 1988, founded precision motor company SmartDrive. He retired on health grounds in the early 2000s.

Dick Greenwood is still in the electronics business. He runs Circuit Solutions (Cambridge), a privately held contract manufacturer.

By the time, Sore left, John Shirreff, was long gone. He left when the administrators came in, a casualty, he hinted, of the job cutting programme. He went on to work for a variety of electronics and programming projects, some as a freelance, others as an employee. Some, such as stint with 80s guitar maker Staccato, combined his love of music and technology. He also returned to the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Oxfordshire - he’d worked there before, in the early 1970s - to work on 3D graphical visualisations of scientific data. Today, semi-retired, he’s looking forward to getting hold of a Raspberry Pi. ®

The author would like to thank the many retro-tech fans for archiving home computing adverts, photos and documentation from the 1980s, without whom this feature would not be possible. Very special thanks go to Geoff Sore and John Shirreff.