Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/07/16/netware_4_anniversary/

How the clammy claws of Novell NetWare were torn from today's networks

In a parallel universe, the LAN king would have crushed Microsoft

Posted in OSes, 16th July 2013 10:38 GMT

Anniversary Before the internet, local area networks were the big thing. A company called Novell was the first to exploit the trend for connecting systems, ultimately becoming "the LAN king" with its NetWare server operating system.

There were alternatives to Novell and NetWare in the 1990s - 3Com’s 3+Share, for example – but such was its appeal that Novell’s share of the LAN market topped 63 per cent at its high point.

Such scale cannot go unnoticed and it caught the interest of Microsoft – then just a PC operating system maker with Office apps. Bill Gates and his team quickly realised they had to build their own server operating system if the were really serious about growing their new company.

In April 1993, Novell released NetWare 4.0, the version that really made the company - and broke it. Twenty years on, it's not Novell or NetWare we talk about on the server: it’s Microsoft and Windows Server - and Linux.

NDS: Killer feature or SMB killjoy?

NetWare 4 was a major upgrade: a native Intel 80386 “NOS” (Network Operating System), like NetWare 3 before it, but now with built-in TCP/IP and better support for applications running on the server.

The big difference, though, was NDS – NetWare Directory Services, a distributed network directory. This was a killer feature for larger multi-site or even multi-server networks, but it was also a killjoy for small business network admins.

The first version of NetWare was a resolutely single-server product – it didn’t even allow multiple servers on a single network. NetWare 1 originally ran on Novell’s proprietary 68000-based server and used a proprietary connection, S-Net, but it offered a compelling advantage over the other early networking systems: file sharing, as opposed to disk sharing.

Rather than splitting up an expensive hard disk into multiple separate segments, one per workstation, NetWare allowed all workstation to access individual files on a single shared volume.

At the time, this wasn’t an obvious idea, but it was soon legitimised by the otherwise-unsuccessful IBM PC LAN. Using a file server meant that PCs could share data with one another, for example permitting the first network-aware PC program of any kind – Novell’s network game SNIPES.

As the networking market grew, Novell ported NetWare to the IBM PC-XT – the upmarket model, with a hard disk as standard – and opened it up to support a dozen other networking systems, including Corvus Omninet, Datapoint ARCnet and 3Com’s new and very expensive Ethernet.

NetWare 2 was a radical rewrite, and one of the first native OSes for Intel’s then new 16-bit CPU, the 80286.

Member when... Intel's 16-bit x86 microprocessor. Image via CPU Collection of Konstantin Lanzet, licensed under Creative Commons

NetWare 2 supported 16MB of server memory and even able to multitask with a copy of MS-DOS for non-dedicated operation. However, it was a pain to install and configure: it was supplied on more than 20 floppy discs and requiring Novell’s proprietary kernel to be re-linked for any configuration change – a lengthy session of “diskaerobics”.

NetWare 3 was the biggest rewrite NetWare would ever get. The OS was modularised, with a kernel and separate NetWare Loadable Modules (NLMs) providing additional functionality. This meant that your NetWare file and print server could also now handle email, for instance. NetWare 3 also offered System Fault Tolerance Level III – the ability to mirror a pair of NetWare servers in a shared-nothing cluster.

NetWare 3 also removed an obscure ability that NetWare 2 had, the significance of which would only appear much later. NetWare 2 could “cold boot”: the OS was able to load itself from a bootable NetWare system volume. NetWare 3 was an MS-DOS executable: your server booted from a DOS partition, or even a DOS floppy, and at the end of AUTOEXEC.BAT you ran SERVER.EXE. DOS remained in RAM unless removed and was needed if you wanted to access files on floppy diskette.

NetWare was now a serious product, ready for prime time – but its authentication system remained a weakness. NetWare’s “Bindery Services” comprised a standalone authentication database, meaning that users had to log on to multiple servers separately – and admins had to maintain separate user lists on every server. “NetWare Name Services” alleviated this as the single database could be extended across multiple servers, but this rapidly became unmanageable for large organisations with multiple sites, particularly if these were in different countries.

This was the problem that NetWare 4 was designed to solve. NDS was a distributed network directory based on the CCITT X.500 standard. A single directory tree would span your entire organisation, with branches containing servers, workstations, users, groups and any other entity whose security you needed to control. Banyan’s VINES had been offering this for years with StreetTalk, but it was a specialist product, whereas NetWare was the leading PC server OS.

What NDS offered was brilliant – it was vastly ahead of Microsoft’s domain security model, as used in OS/2 LAN Manager and Windows NT Server 3.1, also released in 1993.

Windows NT: Simple is good

However, if all you had was a single server, it was also overkill: you had to have a tree, even if it only had one branch. Server admins cursed and hated it for the considerable extra workload it imposed compared to NetWare 3.

Feeling blue? Novell NetWare 4

But that wasn’t NetWare 4’s only problem. The other was Windows NT, from Microsoft.

NetWare 4 itself was the most versatile NOS Novell had ever offered – its range of NLMs added significant extra functionality – but it was still built around file and printer sharing. For instance, when NetWare mounted a disk drive, it stored the entire FAT in RAM. The relationship was linear: the bigger the disk, the more RAM required, or you couldn’t mount it.

If you wanted app servers too, that meant yet more server RAM. And all these processes ran in Ring 0, meaning that a bug in any module caused the whole server to ABEND*. In other words, your server would hang

Windows NT, on the other hand, was a general-purpose OS that natively spoke TCP/IP – or Internet Protocol as we used to call it. It had the familiar Windows user interface, as opposed to the remote-server-console admin of NetWare.

The first version of NT, disingenuously called Windows NT 3.1, was quite immature, but adding additional server functionality was much easier (and often cheaper) on Windows NT than on NetWare.

The golden version of NetWare 4 was really 4.11, dubbed IntraNetWare by Novell's marketdroids in 1996. Out of the box it could act as a web server, a proxy gateway and firewall and more - for a price, of course. There were also – finally – graphical server admin tools that ran on Windows.

But by then, Windows NT 3.51 was out – a really solid, stable version, albeit with the retro Windows 3.1 GUI.

For a small network, NT was a much easier and more flexible server and there was no need to muck around with a network directory: for just a few servers on a single site, domains were much easier. In July 1996, along came NT 4.0, which added the Windows 95 Explorer to NT.

Domains quickly became a liability if you had lots of Windows servers, or a large, multi-site network, where NDS came into its own, but the battle was over.

By 1995, Windows NT was a capable server OS as well as a client, handling file and print and application services with equal facility. Meanwhile, the World Wide Web was forcing a rapid adoption of Internet protocols, which NT handled natively but that were awkward bolt ons to NetWare.

Linux: Mmm, cheap and tasty

Ubiquitous connection to the internet also brought Windows’ many security issues into sharp focus, but by the time of NetWare 4.11 and NT 4, another new server OS was becoming viable: Linux. It needed a skilled techie to wrestle it into submission, but as a cheap, secure firewall or Web server, it was unbeatable.

NetWare didn’t die, but it started to fade away. In 1998, NetWare 5 featured native TCP/IP and Java-based server apps, including a GUI on the server itself. The new NetWare Storage Services filesystem finally broke the linear relationship between disk size and server RAM.

The last version of NetWare was 6.5 in 2003. NetWare now supported many Unix-like services and features, for easier Linux interoperability – but more to the point, all the NetWare server functionality could also run identically on SUSE Linux Enterprise Server. In the Novell Open Enterprise Server box, you got both products, one based on NetWare and one on Linux.

Novell didn't die either. Not exactly. It hired former Sun Microsystems' chief technology officer Eric Schmidt - yes that Eric Schmidt - as chief executive to take it into the internet era. It also bought open-source apps and SuSE Linux to move into open source and Linux. The company also signed a patent-licensing agreement with Microsoft to help sales of that SuSE Linux distro by shielding users from any patent claims by Microsoft.

All the time, though, the momentum behind Novell business as a whole was downwards. Schmidt joined Google, Novell annoyed open-sourcers and enterprise software holding company Attachmate eventually bought Novell for $2.2bn in late 2010.

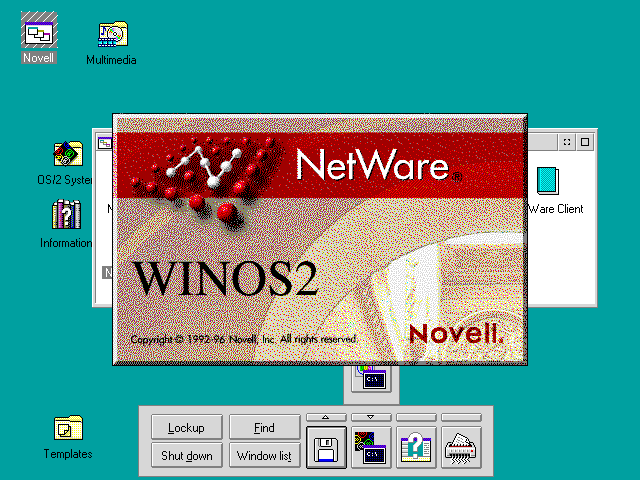

Looking back, what could have been one of NetWare 4’s key features, though, was that peculiarity of booting from MS-DOS. Soon after launch, NetWare 4.01 gained support for another host OS: IBM OS/2 2.

A splash screen added to Win-OS/2 by the Novell NetWare client. Image by Michal Necasek, os2museum.com

But as OS/2 was a proper multitasking 386 OS in its own right, NetWare for OS/2 conferred all sorts of useful abilities to NetWare – such as the ability to run the server and the client (with its admin tools) on the same machine, plus running DOS and OS/2 server applications outside of NetWare while still providing the same high-performance NetWare services.

As OS/2's security was based on domains just like NT's, NDS was a valuable enhancement, too.

Of course, OS/2 itself flopped, so none of this ever mattered, but with hindsight, it was an excellent answer to the threat from Windows NT. If it had been marketed correctly, it could have benefited both products.

NetWare was almost uniquely a thing of its time. Whereas the PC has transcended its roots as a slightly shonky take on the Apple II, and Windows has grown from a limited CP/M-lookalike into a sophisticated 64-bit OS, NetWare never escaped as its niche.

When Windows was just a client OS, Novell’s proprietary IPX/SPX protocol and simple, fast, semi-dedicated file servers were a compelling offering. As Windows grew into a server OS too, though, NetWare couldn't compete. ®

* Abnormal termination (end) of software.