This article is more than 1 year old

Info-saturated techie builds bug alert service that phones you to warn of new vulns

Or SMSes, if the idea of midnight robot calls worries you

An infosec pro fed up of having to follow tedious Twitter accounts to stay on top of cybersecurity developments has set up a website that phones you if there's a new vuln you really need to know about.

Bugalert, founded by product manager Matt Sullivan, is a crowdsourced venture that he hopes will take the pain out of trying to tell the signal from the noise when security researchers make high-impact vulnerability disclosures.

Keeping up with fast-developing situations, such as the Log4j vuln and its iterations, is "extraordinarily overwhelming," he told The Register – and he reckons relying on CVE number assignations is just too slow in this day and age. (It took around a day and a half for the initial Log4j vuln to be given a CVE in November 2021, before an exploit made its way onto Twitter a week later.)

"You know, I'm reading about this vulnerability," sighed Sullivan as he described the Log4j frustration that led to Bugalert. "It's midnight in my time zone. And this tweet had gone out at nine in the morning in my local time, saying that there had been this catastrophic issue. And I found myself extraordinarily frustrated that somebody had a 15-hour lead time and we couldn't, you know, get the word out."

There will be very few people in infosec who don't recognise that problem. If you follow the right pseudonymous Twitter accounts, you can gain crucial hours or even minutes when a new vuln becomes public knowledge. Folk who rarely look away from Twitter are even more likely to spot a new vuln needing immediate remedial action – while those who insist on having lives in meatspace (or even sleeping, the weirdos) can be left behind.

Sullivan described Bugalert as depending on vetted volunteers ("somebody who has depth of experience in the industry, to know if something's a big deal or not") who send push alerts to registered subscribers.

People do this via Bugalert's GitHub page, explained its founder, saying this lets him "select a number of repository maintainers who are geographically dispersed" for round-the-clock coverage. As for the process, it sounds very simple: "When they see that a notice is needing to be reviewed and to be merged in, which will trigger the alert process, they can react to those."

It's an intentionally human-dependent process so far and doesn't rely on ingesting or digesting traditional threat intelligence feeds. With that in mind, what's the difference between Bugalert and traditional mailing lists or RSS feeds?

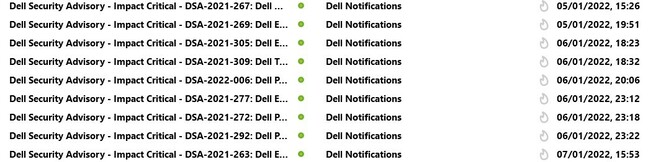

Critical notifications sent by Dell to enterprise customers

Mailing lists, as their name suggests, send emails. "I don't know about you, but my email is a disaster," said Sullivan semi-seriously. "Pressing things and email are not a good mixture for me."

The other problem with mailing lists, in his view, is that vuln notification services from vendors "are held to a very high standard of accuracy."

Sometimes it's more important to quickly apply mitigations than to spend time being precisely correct about the way a particular vuln affects certain environments or deployments.

"I think it's reasonable that you alert someone, saying 'there is an issue, and we don't know how to tell you to fix it'. But your job now is to be aware of it and at least detect it," explained Sullivan.

In his vision, Bugalert-subscribing organisations will receive an alert, "grab a cup of tea while their build completes," increment their product's version number: "And an hour later it's out in production, and they go back to bed."

Very neat on paper. But what of the telephone option? If you sign up for that, Bugalert will call your phone and play a text-to-speech version of a vuln alert created by one of Bugalert's volunteer bug triagers. Sullivan said he imagined users saving Bugalert's phone number and allowing it to bypass their Do Not Disturb settings, something El Reg thinks might be a little fanciful.

More concretely, however, he estimated about three-quarters of Bugalert's 600 current subscribers have signed up for SMS alerts: "There's clearly value there. People are again saying 'My email is not enough, I need something that's a little bit more direct for me'… people are sure interested in early notification, but they're also interested in different types of notification than they currently are receiving."

- Miscreants started scanning for Exchange Hafnium vulns five minutes after Microsoft told world about zero-days

- Four million outdated Log4j downloads were served from Apache Maven Central alone despite vuln publicity blitz

- Just 2.6% of 2019's 18,000 tracked vulnerabilities were actively exploited in the wild

- We regret to inform you there's an RCE vuln in old version of WinRAR. Yes, the file decompression utility

Industry reaction has been mixed, with a Reddit thread about Bugalert containing both praise and informed criticism. One poster observed: "You built an infrastructure to send emails/SMS but you are also looking for volunteers to report, triage, validate, and approve vulnerabilities. The volunteer phase is what CVE is doing, albeit too slowly."

As for funding, so far it's all dependent on Sullivan's bank account. He told us he'd consider financial contributions or sponsorship in the future but rejected the idea of sticking up banner ads, something that'll doubtless please Vulture Central's backroom gremlins.

Some won't see the value of this project, arguing Bugalert reproduces any number of notification mechanisms. Others will be horrified at the idea of strangers being able to wake them up with robots reading words down their phones in the middle of the night. Nonetheless, a few hundred sysadmins out there think it fills a niche. ®