This article is more than 1 year old

Britain’s forgotten first home computer pioneer: John Miller-Kirkpatrick

The electronics genius who nearly beat Clive Sinclair at his own game

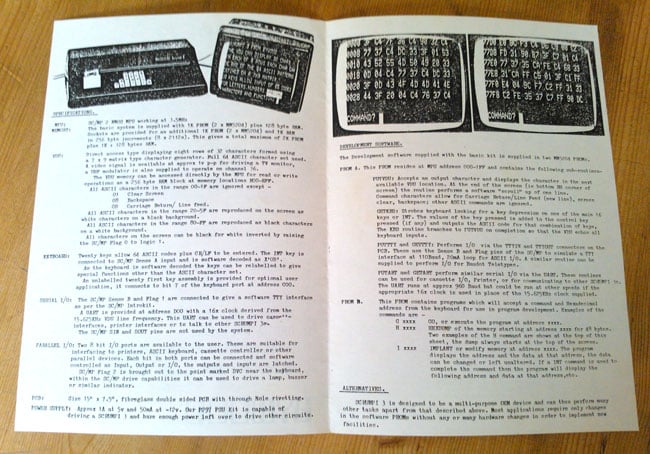

Scrumpi Mk 3

Overall, however, the Scrumpi 3 “is nicely produced, fulfils its designers’ requirements and the distributor, Bywood Electronics, are very helpful in the event of any difficulties or problems”.

Customers included “universities, a photographic equipment maker, an airport cargo/passenger scheduling company”, Miller-Kirkpatrick wrote shortly afterwards. Even Sinclair Radionics wanted one, to help demo its personal digital multimeters and 2-inch Microvision pocket TVs at electronics shows.

The third-generation Scrumpi had a 4KB memory map - the furthest the SC/MP-II could go with its 12 address lines - so with 1024 bytes allocated to the VDU, keyboard, UART and other ports, Miller-Kirkpatrick had a further 3KB of addresses to play with: 1KB went on the on-board software monitor, held in ROM, and the rest was linked to two slots, one to take an optional 1KB of RAM, the other for 1KB of extra PROM.

Scrumpi 3 could be yours for £155 - or £190 if you had the cased version, which also incorporated a microcassette recorder for program storage. There was no Basic interpreter, but Miller-Kirkpatrick had a mind to offer one and may even have started work on the software. It might not have been the complete home computer system the Nascom 1 was, but it was considerably cheaper.

“Whether we like it or not, microprocessors are going to enter our everyday life the same way that transistors have done,” Miller-Kirkpatrick wrote that year. It was clear from his journalism he knew the microcomputer revolution had begun and that he wanted to be a part of it.

But that was not to be.

Anticipating the revolution

Quite apart from his illness and the need to bring up two children - with wife Jane out at the Bywood office every day, sorting out the kids every morning and after school fell to John, and he also "home schooled" young Ashleigh for a year - it was a tough time for the electronics and nascent computing business in the UK.

“At present the UK boasts something like six companies making home and small business computers based on microprocessors, my own company being one of them,” he wrote and told the recently launched Personal Computer World around the middle of 1978. “Recently we had 95 per cent of our kits waiting on the shelves for three months due to the ‘memory famine’. During that time, we had to watch the customers dwindle and the bank overdraft charges rise.

“We will soon be able to deliver from stock, but the majority of advertising and selling done three and four months ago has been wasted. Other UK companies are in similar situations for various reasons.”

Miller-Kirkpatrick was writing in response to readers who had been grumbling about the generally high price of computers in the UK compared to those available in the US. Even 35 years ago, this aspect of "rip-off Britain" was bothering technology buffs, just as it still does.

Hard times

John’s rebuttal was clearly put: “There has been some controversy recently concerning the price of American MPU systems in the UK. There are companies who simply change the $ sign for a £ sign and call that the UK price; most are more reasonable.” What many folk forget, he said, is the differences between Britain and America.

“Let us take as an example a reasonably sized American microcomputer system which sells for a basic $2,000. Sales volumes are low because of the relatively high prices of the equipment in the UK. Even if the UK dealer made no profit and sold the example system for £1,000, this probably represents a quarter of the average annual salary for a programmer or engineer, the most likely first customer.

“In the US, the typical engineer or programmer can expect to get about $20,000 per annum; our $2000 example is equivalent to only one tenth of his salary.”

Chalk... and cheese: in the mid-1970s, the brash Electronics Today (right) was very different from the staid Practical Electronics (left)

Microcomputers were only going to be popular, then, if they became much cheaper. Thanks to Clive Sinclair, they soon would be. But John Miller-Kirkpatrick, who with the Scrumpi series had established the notion of low-cost but functional computer for everyone, would not witness the explosion in interest in home microcomputers to come.

Toward the end of 1978, Miller-Kirkpatrick’s illness took a turn for the worse. By now Jane Miller-Kirkpatrick had been forced to spend less time on Bywood. In order to make ends meet, she had studied accountancy part time and then set up a bookkeeping business. But perhaps she and John also understood she would need to call on such a practical skill when eventually her husband would no longer be able to contribute the articles and electronics designs that had kept Bywood in business.

The leukaemia became more severe, and on 12 December 1978 Miller-Kirkpatrick died. He was only 32 years old.